جاگرافي

جاگرافي (geography) يوناني ٻولي جو لفظ آهي. جنهن جي معنيٰ آهي زمين جو بيان. جاگرافي اهو علم آهي، جن ۾ زمين، انجي خصوصيتن، انجي باشندن، انجيُ مظهرن ۽ اُن جي نقشن جو اڀياس ڪيو ويندو آهي. جاگرافي هڪ تمام وسيع نظم و ضبط آهي جيڪو ڌرتيءَ ۽ ان جي انسان ۽ قدرتي پيچيدگين کي سمجهڻ جي ڪوشش ڪري ٿي؛ نه رڳو اهي شيون ڪٿي آهن، پر اهو پڻ آهي ته اهي ڪيئن بدلجي ويون آهن. جڏهن ته جاگرافي ڌرتيءَ لاءِ مخصوص آهي، ڪيترن ئي تصورن کي ڌرتيءَ جي سائنس جي ميدان ۾ ٻين آسماني جسمن تي وڌيڪ وسيع طور تي لاڳو ڪري سگهجي ٿو. جاگرافي کي، "قدرتي سائنس ۽ سماجي سائنس جي وچ ۾ هڪ پل" سڏيو ويو آهي. جاگرافي (قديم يوناني لفظن، "γεωγραφία"؛ جيو: زمين ۽ گرافيا: لکڻ کي گڏ ڪندي) ڌرتيءَ جي علائقن جي خاصيتن، رهاڪن ۽ واقعن جو مطالعو آهي.

جاگرافي ۾ ڪيترن ئي تصورن جي اصليت يوناني، سائرين جي ايراٽسٿنيز ( 276 – 195 ق.م) ۾ ملي سگهي ٿي، جنهن شايد لفظ، "γεωγραφία" (جيوگرافيا) جوڙيو هوندو. لفظ، جيوگرافيا (γεωγραφία) جو پهريون رڪارڊ ٿيل استعمال يوناني اسڪالر ڪلاڊيئس ٽالمي (100 - 170ع) جي ڪتاب جي عنوان سان هو. هن ڪم جغرافيائي جي نام نهاد "ٽولمي روايت" پيدا ڪئي، جنهن ۾ "ٽولمي ڪارٽوگرافڪ نظريو" شامل آهي. بهرحال، جاگرافي جا تصور (جهڙوڪ نقش نگاري) دنيا کي مقامي طور تي سمجهڻ جي ابتدائي ڪوششن کان وٺي، قديم بابل ۾ 9هين صدي قبل مسيح جي تاريخ جي دنيا جي نقشي جي شروعاتي مثال سان، جاگرافي جي تاريخ هڪ نظم و ضبط جي طور تي ثقافتن ۽ هزارين سالن تائين پکڙيل آهي، ڪيترن ئي گروهن پاران آزاديء سان ترقي ڪئي وئي آهي، ۽ انهن گروهن جي وچ ۾ واپار جي ذريعي پار پولينٽ ڪيو ويو آهي. جاگرافي جا بنيادي تصور سڀني نقطن جي وچ ۾ هڪجهڙائي، جڳهه، وقت ۽ پيماني تي ڌيان ڏيڻ وارا آهن.

اڄ، جغرافيائي ڪيترن ئي ماڊل ۽ طريقن سان هڪ انتهائي وسيع نظم و ضبط آهي. نظم و ضبط کي منظم ڪرڻ لاءِ ڪيتريون ئي ڪوششون ڪيون ويون آهن، جن ۾ جغرافيائي جون چار روايتون ۽ شاخون شامل آهن. پيشي جي لحاظ کان ٽيڪنالاجيون عام طور تي، ڪيترن ئي مطالعي سان مخلوط طريقن سان مقدار ۽ معيار جي طريقن ۾ ورهائي سگهجن ٿيون. عام ٽيڪنالاجي ۾ ڪارٽوگرافي، ريموٽ سينسنگ ۽ سروينگ شامل آهن.

جاگرافي جون شاخون

[سنواريو]بنيادي اصول

[سنواريو]

جاگرافي ڌرتيءَ جو هڪ منظم مطالعو آهي (ٻين فلڪي جسم جي وضاحت ڪئي وئي آهي، جهڙوڪ "مريخ جي جاگرافي"، يا ٻيو نالو ڏنو ويو آهي، جيئن ته مريخ جي صورت ۾ آروگرافي)، ان جون خاصيتون ۽ واقعا جيڪي ان تي ٿين ٿا.[1][2][3]

ڪنهن به شيءِ لاءِ جاگرافي جي ڊومين ۾ اچڻ لاءِ، ان کي عام طور تي ڪجهه قسم جي فضائي جزن، جهڙوڪ ڪوآرڊينيٽس، هنڌ جا نالا، يا پتا، جي ضرورت هوندي آهي جيڪا نقشي تي رکي سگهجن ٿيون، ان ڪري جغرافيائي نقشا نگاري ۽ هنڌن جي نالن سان جڙيل آهي. جيتوڻيڪ ڪيترن ئي جاگرافيدانن کي ٽوپونومي ۽ ڪارٽولوجي ۾ تربيت ڏني وئي آهي، اهو انهن جو بنيادي ڪم نه آهي. جاگرافيدان ڌرتيءَ جي فضائي ۽ عارضي ورهاڱي، واقعن، عملن ۽ خاصيتن سان گڏوگڏ انسانن ۽ انهن جي ماحول جي رابطي جو مطالعو ڪن ٿا.[4] ڇاڪاڻ ته جڳهون مختلف عنوانن، جهڙوڪ اقتصاديات، صحت، آبهوا، نباتات ۽ جانور تي اثر انداز ٿيڻ ٿيون. جاگرافي انتهائي بين الاقوامي موضوع آهي. جغرافيائي انداز جي بين الاقوامي نوعيت جو دارومدار طبيعي ۽ انساني رجحان ۽ انهن جي فضائي نمونن جي وچ ۾ تعلق تي ڌيان ڏيڻ تي آهي.[5]

جڳهن جا نالا... جاگرافي نه آهي... دل سان ڄاڻڻ لاءِ انهن سان ڀريل هڪ مڪمل گزيٽيئر، پاڻ ۾، ڪنهن کي به جاگرافي دان نه بڻائيندو. جاگرافيءَ جا هن کان وڌيڪ اعليٰ مقصد آهن: اهو رجحان جي درجي بندي، فطرت جي قانونن کي ڳولڻ ۽ انسان تي انهن جي اثرن کي نشانو بڻائڻ لاء، اثرات کان سببن ڏانهن وڌڻ (جنهن جي لحاظ کان قدرتي ۽ سياسي دنيا جي، جيئن ته اهو بعد ۾ علاج ڪري ٿو)، موازنو ڪرڻ، عام ڪرڻ ۾ چاهي ٿي. هي آهي ’دنيا جو بيان‘ يعني جاگرافي. هڪ لفظ ۾، جاگرافي؛ هڪ شيءِ رڳو نالن جي نه پر دليل، سبب ۽ اثر جي هڪ سائنس آهي.[6]

— وليم هيوز، 1863ع

جاگرافي کي هڪ نظم جي طور تي وسيع طور تي ٽن مکيه شاخن ۾ ورهائي سگهجي ٿو: انساني جاگرافي، طبيعي جاگرافي ۽ ٽيڪنيڪل جاگرافي.[7] انساني جاگرافي گهڻو ڪري تعمير ٿيل ماحول ۽ هن کي انسان ڪيئن ٺاهيا ۽ ڪيئن هي ماحول خلا تي اثر انداز ڪري ٿو، ڏسڻ ۽ منظم ڪرڻ تي ڌيان ڏئي ٿي.[8] طبيعي جاگرافي قدرتي ماحول کي جانچيندي آهي ۽ ڪيئن جاندار، آبهوا، مٽي، پاڻي، ۽ زميني شڪلون پيدا ٿين ٿيون ۽ ڪئين لهه وچڙ ۾ اچن ٿيون.[9] انهن نقطن جي وچ ۾ فرق مربوط جاگرافي جي ترقي جو سبب بڻيو، جيڪو طبيعي ۽ انساني جاگرافي کي گڏ ڪري ٿو ۽ ماحول ۽ انسانن جي وچ ۾ رابطي جي متعلق آهي.[10] ٽيڪنيڪل جاگرافي ۾ جاگرافيدانن پاران استعمال ڪيل اوزارن ۽ ٽيڪنالاجي جو مطالعو ۽ ترقي ڪرڻ شامل آهي، جهڙوڪ ريموٽ سينسنگ، ڪارٽوگرافي ۽ جاگرافيائي ڄاڻ وارو نظام.[11]

اهم تصورات

[سنواريو]جاگرافي کي ڪجهه اهم تصورن تائين محدود ڪرڻ انتهائي مشڪل آهي ۽ نظم و ضبط جي اندر زبردست بحث جي تابع آهي.[12] ھڪڙي ڪوشش ۾، ڪتاب، "جاگرافي ۾ اھم تصور" جو پھريون ايڊيشن، ھن کي، "خلا"، "جڳھ"، "وقت"، "پيمانو" ۽ "زمين جي تزئين" تي ڌيان ڏيڻ، بابن ۾ ورهايو.[13] ڪتاب جو ٻيو ايڊيشن، "ماحولياتي نظام"، "سماجي نظام"، "فطرت"، "ترقي"، "گلوبلائيزيشن" ۽ "خدشن" کي شامل ڪندي، انهن اهم تصورن کي وڌايو، اهو ڏيکاري ٿو ته جاگرافي جي ميدان کي تنگ ڪرڻ ڪيترو مشڪل ٿي سگهي ٿو.[14]

Another approach used extensively in teaching geography are the Five themes of geography established by "Guidelines for Geographic Education: Elementary and Secondary Schools," published jointly by the National Council for Geographic Education and the Association of American Geographers in 1984.[15][16] These themes are Location, place, relationships within places (often summarized as Human-Environment Interaction), movement, and regions.[16][17] The five themes of geography have shaped how American education approaches the topic in the years since.[16][17]

Space

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Space

Just as all phenomena exist in time and thus have a history, they also exist in space and have a geography.[18]

For something to exist in the realm of geography, it must be able to be described spatially.[18][19] Thus, space is the most fundamental concept at the foundation of geography.[20][21] The concept is so basic, that geographers often have difficulty defining exactly what it is. Absolute space is the exact site, or spatial coordinates, of objects, persons, places, or phenomena under investigation.[20] We exist in space.[22] Absolute space leads to the view of the world as a photograph, with everything frozen in place when the coordinates were recorded. Today, geographers are trained to recognize the world as a dynamic space where all processes interact and take place, rather than a static image on a map.[20][23]

Place

[سنواريو]

Place is one of the most complex and important terms in geography.[22][25][26][27] In human geography, place is the synthesis of the coordinates on the Earth's surface, the activity and use that occurs, has occurred, and will occur at the coordinates, and the meaning ascribed to the space by human individuals and groups.[19][26] This can be extraordinarily complex, as different spaces may have different uses at different times and mean different things to different people. In physical geography, a place includes all of the physical phenomena that occur in space, including the lithosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere.[27] Places do not exist in a vacuum and instead have complex spatial relationships with each other, and place is concerned how a location is situated in relation to all other locations.[28][29] As a discipline then, the term place in geography includes all spatial phenomena occurring at a location, the diverse uses and meanings humans ascribe to that location, and how that location impacts and is impacted by all other locations on Earth.[26][27] In one of Yi-Fu Tuan's papers, he explains that in his view, geography is the study of Earth as a home for humanity, and thus place and the complex meaning behind the term is central to the discipline of geography.[25]

Time

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون/مضمونن جي لاءِ ڏسو Time geography ۽ Historical geography

Time is usually thought to be within the domain of history, however, it is of significant concern in the discipline of geography.[30][31][32] In physics, space and time are not separated, and are combined into the concept of spacetime.[33] Geography is subject to the laws of physics, and in studying things that occur in space, time must be considered. Time in geography is more than just the historical record of events that occurred at various discrete coordinates; but also includes modeling the dynamic movement of people, organisms, and things through space.[22] Time facilitates movement through space, ultimately allowing things to flow through a system.[30] The amount of time an individual, or group of people, spends in a place will often shape their attachment and perspective to that place.[22] Time constrains the possible paths that can be taken through space, given a starting point, possible routes, and rate of travel.[34] Visualizing time over space is challenging in terms of cartography, and includes Space-Prism, advanced 3D geovisualizations, and animated maps.[28][34][35][23]

Scale

[سنواريو]

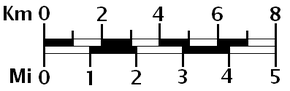

Scale in the context of a map is the ratio between a distance measured on the map and the corresponding distance as measured on the ground.[36][37] This concept is fundamental to the discipline of geography, not just cartography, in that phenomena being investigated appear different depending on the scale used.[38][39] Scale is the frame that geographers use to measure space, and ultimately to understand a place.[37]

===Laws of geography

===

- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Quantitative geography#Laws of geographyDuring the quantitative revolution, geography shifted to an empirical law-making (nomothetic) approach.[40][41] Several laws of geography have been proposed since then, most notably by Waldo Tobler and can be viewed as a product of the quantitative revolution.[42] In general, some dispute the entire concept of laws in geography and the social sciences.[28][43][44] These criticisms have been addressed by Tobler and others, such as Michael Frank Goodchild.[43][44] However, this is an ongoing source of debate in geography and is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon. Several laws have been proposed, and Tobler's first law of geography is the most generally accepted in geography. Some have argued that geographic laws do not need to be numbered. The existence of a first invites a second, and many have proposed themselves as that. It has also been proposed that Tobler's first law of geography should be moved to the second and replaced with another.[44] A few of the proposed laws of geography are below:

- Tobler's first law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant."[28][43][44]

- Tobler's second law of geography: "The phenomenon external to a geographic area of interest affects what goes on inside."[43][45]

- Arbia's law of geography: "Everything is related to everything else, but things observed at a coarse spatial resolution are more related than things observed at a finer resolution."[38][43][39][46][47]

- Spatial heterogeneity: Geographic variables exhibit uncontrolled variance.[44][48][49]

- The uncertainty principle: "That the geographic world is infinitely complex and that any representation must therefore contain elements of uncertainty, that many definitions used in acquiring geographic data contain elements of vagueness, and that it is impossible to measure location on the Earth's surface exactly."[44]

Additionally, several variations or amendments to these laws exist within the literature, although not as well supported. For example, one paper proposed an amended version of Tobler's first law of geography, referred to in the text as the Tobler–von Thünen law,[42] which states: "Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things, سانچو:Em."[Note 1] [42]

ذيلي مضمون

[سنواريو]طريقا

[سنواريو]اصل ۽ تاريخ

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو جاگرافي جي تاريخ

جاگرافي جو تصور سڀني ثقافتن ۾ موجود آهي، ۽ ان ڪري نظم جي تاريخ مقابلي واري داستانن جو هڪ سلسلو آهي، جيڪا تصورات سان گڏ خلا ۽ وقت جي مختلف نقطي تي اڀري.[50] دنيا جا سڀ کان پراڻا نقشا نائين صدي قبل مسيح کان قديم بابل جا آهن.[51] جڏهن ته بابلي دنيا جو بهترين نقشو، اماگو منڊي (Imago Mundi) 600 ق.م جو آهي، [52] ايڪهارڊ انگر (Eckhard Unger) پاران ٻيهر تعمير ڪيل نقشو فرات ندي جي ڪناري تي بابل کي ڏيکاري ٿو، جنهن جي چوڌاري هڪ گول سرزمين آهي، جنهن جي چوڌاري اسيريا، ارارتو ۽ ڪيترن ئي شهرن کي ڏيکاريل آهي، جنهن جي چوڌاري هڪ "تلخ ندي"، اوشيانس (Oceanus) آهي، جنهن جي چوڌاري ست ٻيٽ ترتيب ڏنل آهن ته جيئن اهي ستن نقطن وارو تارو ٺاهي سگهن.[53] گڏ ٿيل متن ۾ سمنڊ جي چوڌاري ست ٻاهرين علائقن جو ذڪر آهي. انهن مان پنجن جو احوال بچيل آهي.[54] "اماگو منڊي" جي ابتڙ، نائين قبل مسيح جي تاريخ ۾ هڪ اڳوڻي بابلي دنيا جي نقشي ۾ بابل کي دنيا جي مرڪز کان وڌيڪ اتر جي طور تي ظاهر ڪيو ويو آهي، جيتوڻيڪ اها پڪ ناهي ته اهو مرڪز ڪهڙي جاء جي نمائندگي ڪري ٿو.[55]

اناگزيمئنڊر (Anaximander) (610-545 ق. م) جا خيال، بعد ۾ يوناني ليکڪن پاران جاگرافيءَ جو سچو باني سمجھيو ويو، اسان وٽ سندس جانشين پاران ٽڪرن جي ذريعي آيا آهن.[56] اناگزيمئنڊر کي گنومون، سادو، اڃا تائين ڪارائتو يوناني اوزار جيڪو ويڪرائي ڦاڪ جي شروعاتي ماپ جي اجازت ڏني، جي ايجاد سان منسوب ڪيو ويو آهي.[57] ٿيلس کي پڻ گرهن جي اڳڪٿي سان اعتبار ڪيو ويندو آهي. جاگرافي جا بنياد قديم ثقافتن، جهڙوڪ قديم، وسطي ۽ جديد شروعاتي چيني ثقافت ۾ ڳولي سگهجو ٿا. يوناني، جن جاگرافي کي فن ۽ سائنس ٻنهي جي طور تي دريافت ڪرڻ وارا پهريان هئا، اهو ڪارٽوگرافي، فلسفو ۽ ادب يا رياضي جي ذريعي حاصل ڪيو. ان بابت ڪجهه بحث آهي ته پهريون شخص ڪير هو جنهن اهو دعويٰ ڪيو ته ڌرتيءَ جي شڪل گول آهي، جنهن جو ڪريڊٽ يا ته پرمينائيڊس يا پيٿاگورس کي وڃي ٿو. ايناگزا گورس، گرھڻ جي وضاحت ڪندي، ظاھر ڪرڻ جي قابل ٿي ويو ته ڌرتيء جي پروفائل کي گول ڪيو ويو آھي. بهرحال، هن اڃا تائين يقين ڪيو ته ڌرتي هڪ هموار ٿالي وانگر آهي، جيئن هن جا ڪيترائي همعصر ان جا قائل هئا. ڌرتيءَ جي نصف قطر (Radius) جو پهريون اندازو ايراٽوسيٿنس ڪيو.[58]

ويڪرائي ڦاڪ ۽ ڊگھائي لڪيرن جو پهريون سخت نظام هپارڪس ڏانهن منسوب ڪيو ويو آهي. هن هڪ ڇهه انگن (Sexagesimal) جو نظام کي استعمال ڪيو جيڪو بابلين جي رياضي مان نڪتل هو. ميريڊين کي °360 ڊگرين ۾ ورهايو ويو ۽ هر ڊگري کي وڌيڪ 60 (منٽ) ۾ ورهايو ويو. ڌرتيءَ تي مختلف هنڌن تي ڊگھائي ڦاڪ کي ماپڻ لاءِ، هن وقت ۾ لاڳاپا فرق کي طئي ڪرڻ لاءِ گرهن جي استعمال ڪرڻ جي صلاح ڏني.[59] روميئن پاران وسيع نقشي سازي جيئن ته انهن نئين زمينن جي ڳولا ڪئي، بعد ۾ ٽالمي لاءِ تفصيلي ائٽلس تعمير ڪرڻ لاءِ اعليٰ سطحي معلومات فراهم ڪئي. هن پنهنجي نقشن تي گرڊ سسٽم استعمال ڪندي هپارڪس جي ڪم کي وڌايو ۽ هڪ ڊگري لاءِ 56.5 ميل جي ڊيگهه اختيار ڪئي.[60]

ٽين صدي عيسويءَ کان پوءِ، جاگرافيائي اڀياس جا چيني طريقا ۽ جاگرافيائي ادب جي لکڻين ان وقت (13هين صدي عيسويءَ تائين) يورپ ۾ موجود طريقن کان وڌيڪ جامع ٿي ويا.[61] چيني جاگرافيدان جهڙوڪ ليو اين، پيئي شيائو، جيا ڊان، شين ڪائو، فان چينگڊا، زائو ڊگوان ۽ سو شيڪ اهم ڪارناما لکيا، پر پوءِ به 17هين صديءَ تائين چين مغربي طرز جي جاگرافي جا جديد نظريا ۽ طريقا اختيار ڪري چڪو هو.

وچين دور ۾، رومي سلطنت جي زوال جي نتيجي ۾ جاگرافي جي ارتقا يورپ کان اسلامي دنيا ۾ منتقل ٿي وئي.[62] مسلمان جاگرافيدان جيئن ته محمد الادريسيءَ دنيا جا تفصيلي نقشا تيار ڪيا (جهڙوڪ ٽيبيولا روجيريانا)، جڏهن ته ٻين جاگرافي دان جهڙوڪ ياقوت الحموي، ابو ريحان البيروني، ابن بطوطه ۽ ابن خلدون پنهنجي سفرن جا تفصيلي احوال ۽ سنڌ جي جاگرافيائي ڄاڻ ڏني. انهن علائقن جو دورو ڪيو. ترڪي جي جاگرافيدان محمود الڪاشغري لساني بنيادن تي دنيا جو نقشو ٺاھيو ۽ اڳتي هلي پيري ريس (پيري ريس جو نقشو) پڻ هن ريت نقشو ٺاھيو. ان کان سواءِ اسلامي عالمن رومن ۽ يونانين جي اڳين ڪمن جو ترجمو ۽ تفسير ڪيو ۽ ان مقصد لاءِ بغداد ۾ "دارالحڪمه" (دانائي جو گھر) قائم ڪيو.[63] ابو زيد البلخي، اصل ۾ بلخ جو رهاڪو هو، هن بغداد ۾ زميني نقشا سازي جي ”بلخي اسڪول“ جو بنياد وڌو. [64] سهراب، ڏهين صديءَ جي آخر ۾ هڪ مسلمان جاگرافيدان، جاگرافيائي ڪوآرڊينيٽس جو هڪ ڪتاب گڏ ڪيو، جنهن ۾ دنيا جو هڪ مستطيل نقشو، هڪ جهڙائي واري پروجئڪشن يا سلنڊريڪل هڪجهڙائي واري پروجئڪشن سان ٺاهيو ويو.[65]

ابو ريحان البيروني (976-1048ع) پهريون ڀيرو آسماني دائري جي هڪ پولر ايڪو-ايزيموٿل برابري واري پروجئڪشن کي بيان ڪيو.[66] شهرن جي نقشي سازي ۽ انهن جي وچ ۾ فاصلن کي ماپڻ ۾ هن کي سڀ کان وڌيڪ ماهر سمجهيو ويندو هو، جيڪو هن وچ اوڀر ۽ هندستان جي ننڊي کنڊ جي ڪيترن ئي شهرن لاء ڪيو. هن اڪثر ڪري فلڪياتي مشاهدي ۽ رياضياتي مساواتن کي گڏ ڪيو ته جيئن ويڪرائي ڦاڪ ۽ ڊگهائي ڦاڪ جي درجن کي رڪارڊ ڪندي پن-پوائنٽنگ جڳهن جا طريقا ٺاهي. هن جبلن جي اوچائي، وادين جي کوٽائي ۽ افق جي وسعت کي ماپڻ لاءِ، پڻ ساڳي ٽيڪنڪ اختيار ڪئي.

هن انساني جاگرافي ۽ ڌرتيءَ جي رهڻي ڪهڻي تي پڻ بحث ڪيو. هن سج جي وڌ ۾ وڌ اوچائي استعمال ڪندي ڪاث، خوارزم جي ويڪرائي ڦاڪ جو به اندازو لڳايو ۽ ڌرتيءَ جي گهيري جي ماپ جي صحيح حساب سان هڪ پيچيده جيوڊيسڪ مساوات کي حل ڪيو، جيڪو ڌرتيءَ جي گهيري جي ماپ جي جديد قدرن جي ويجهو هو.[67] ڌرتيءَ جي نصف قطر (Radius) لاءِ سندس 6,339.9 ڪلوميٽر جو اندازو 6,356.7 ڪلوميٽر جي جديد قدر کان فقط 16.8 ڪلوميٽر گهٽ هو. پنهنجي اڳين جي ابتڙ، جن سج کي ٻن مختلف هنڌن تي هڪ ئي وقت ڏسي ڪري ڌرتيءَ جي گهيري کي ماپيو، البيروني ميداني ۽ جبل جي چوٽيءَ جي وچ واري زاويه جي بنياد تي ٽريگونوميٽرڪ حسابن کي استعمال ڪرڻ جو هڪ نئون طريقو تيار ڪيو، جنهن سان ڌرتي جي گهيري کي وڌيڪ درست ماپون مليون ۽ ان کي ممڪن بڻايو ته ان کي هڪ ئي شخص هڪ ئي هنڌ تي بيٺو ماپي سگهجي.[68]

The European Age of Discovery during the 16th and the 17th centuries, where many new lands were discovered and accounts by European explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Marco Polo, and James Cook revived a desire for both accurate geographic detail and more solid theoretical foundations in Europe. In 1650, the first edition of the Geographia Generalis was published by Bernhardus Varenius, which was later edited and republished by others including Isaac Newton.[69][70] This textbook sought to integrate new scientific discoveries and principles into classical geography and approach the discipline like the other sciences emerging, and is seen by some as the division between ancient and modern geography in the West.[69][70]

The Geographia Generalis contained both theoretical background and practical applications related to ship navigation.[70] The remaining problem facing both explorers and geographers was finding the latitude and longitude of a geographic location. While the problem of latitude was solved long ago, but that of longitude remained; agreeing on what zero meridians should be was only part of the problem. It was left to John Harrison to solve it by inventing the chronometer H-4 in 1760, and later in 1884 for the International Meridian Conference to adopt by convention the Greenwich meridian as zero meridians.[71]

The 18th and 19th centuries were the times when geography became recognized as a discrete academic discipline, and became part of a typical university curriculum in Europe (especially Paris and Berlin). The development of many geographic societies also occurred during the 19th century, with the foundations of the Société de Géographie in 1821, the Royal Geographical Society in 1830, Russian Geographical Society in 1845, American Geographical Society in 1851, the Royal Danish Geographical Society in 1876 and the National Geographic Society in 1888.[72] The influence of Immanuel Kant, Alexander von Humboldt, Carl Ritter, and Paul Vidal de la Blache can be seen as a major turning point in geography from philosophy to an academic subject.[73][74][75][76][77] Geographers such as Richard Hartshorne and Joseph Kerski have regarded both Humboldt and Ritter as the founders of modern geography, as Humboldt and Ritter were the first to establish geography as an independent scientific discipline.[78][79]

Over the past two centuries, the advancements in technology with computers have led to the development of geomatics and new practices such as participant observation and geostatistics being incorporated into geography's portfolio of tools. In the West during the 20th century, the discipline of geography went through four major phases: environmental determinism, regional geography, the quantitative revolution, and critical geography. The strong interdisciplinary links between geography and the sciences of geology and botany, as well as economics, sociology, and demographics, have also grown greatly, especially as a result of earth system science that seeks to understand the world in a holistic view. New concepts and philosophies have emerged from the rapid advancement of computers, quantitative methods, and interdisciplinary approaches. In 1970, Waldo Tobler proposed the first law of geography, "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."[28][29] This law summarizes the first assumption geographers make about the world.

اهو علم مصر ۽ يونان ۾ سائنس جي حيثيت سان شروع ٿيو. قديم جاگرافيدانن جون ڪي لکڻيون ڏاڍيون دلچسپ آهن. مثال طور اسٽرابو، جيڪو اطالوي جاگرافيدان هو، ان جي راءِ هئي ته سمنڊ جو پاڻي ڪنهن وڏي نديءَ وانگر سلوپ (Slope) تائين محدود هوندو آهي.

سڀ کان پهريان يوناني جاگرافي ۾ ترقي ڪيا. ارسطوءَ جو خيال هو ته فضا کان هوا زمين ۾ اچي ڦاسي پوندي آهي ۽ جڏهن اها فضا ۾ واپس ويجهن لاءِ جدوجهد ڪندي آهي ته زلزلا ايندا آهن. پر انهن عجيب خيالن سان گڏ، قديم يونانين ڪجهه عجيب دريافتون ڪيون. مثال طور، تقريبا 200 ق.م، ارسطارتس مصر جي اوڀر ۽ اولهه ۾ لهرن جو تناسب معلوم ڪندي، اهو اعلان ڪيو ويو ته ائٽلانٽڪ سمنڊ ۽ هندي وڏو سمنڊ آپس ۾ ڳنڍيل آهن. سندس هڪ ٻي دريافت به قابل ذڪر آهي، جنهن موجب هن ٻڌايو ته اتر کان ڏکڻ تائين ڏور اولهه ۾ ڪو ملڪ ضرور آهي. سترهن سو سالن پوءِ ڪولمبس هي ملڪ، آمريڪا دريافت ڪيو. اراٽوسٿينز (196-276 ق.م) پهريون فرد هو، جنهن لفظ جاگرافي ڪتب آندو هو.

وچين دور ۾ هي علم مسلم ملڪن ۾ وڏي ترقي ڪئي. هن دور جي اهم نالن ۾ ابن بطوطه، ابن خلدون ۽ محمد الادريسي شامل آهن. مسلمانن جي ذهني زوال کان پوءِ يورپ ۾ ان موضوع تي تمام گهڻي ترقي ٿي. جاگرافيءَ کي ڌرتيءَ جي سائنس جي هڪ شاخ به چيو وڃي ٿو. اڄ تائين انسان جيڪا به اڳڀرائي (ترقي) ڪئي آهي اها جاگرافيءَ جي ئي ڪارڻ آهي. ڌرتي انسانن جو گڏيل گھر آهي ۽ ان گڏيل گھر مان وڌ کان وڌ لاڀ حاصل ڪرڻ لاءِ جاگرافي اسان جي سرواڻي ڪري ٿي. جاگرافيءَ جو علم تمام گھڻو آڳاٽو آهي. پر اڳ ۾ ان جي اهميت ايتري گھڻي ڪونه هئي جيتري هاڻي آهي. اڳ ۾ جاگرافيءَ لاءِ عام طور تي دريائن، جبلن، سمنڊن ۽ ماڳن جا نالا ياد ڪري ڇڏڻ کي وڏي ڳالھ سمجھيو ويندو هو، اهو ئي سبب آهي جو جاگرافيءَ جي علم ۾ ٻين علمن جي ڀيٽ ۾ اڳڀرائي گھڻي حد تائين ڍرائي سان ٿي آهي.

قابل ذڪر جاگرافيدان

[سنواريو]ادارا ۽ سماج

[سنواريو]اشاعتون

[سنواريو]لاڳاپيل شعبا

[سنواريو]گيلري

[سنواريو]

پڻ ڏسو

[سنواريو]خارجي لنڪس

[سنواريو]| جاگرافي بابت وڌيڪ ڏسو وڪيپيڊيا جي ڀينر رٿائن ۾: | |

| معني ڏسو وِڪِشنري تي | |

| تصويرون ۽ وڊيو ڏسو وڪي ڪامنز تي | |

| تربيتي مواد ڏسو وڪي ورسٽي تي | |

| نيوز اسٽوريز وڪي نيوز تان | |

| چَوِڻيون Quotations وڪي ڪوٽ تان | |

| سورس ٽيڪسٽس وڪي سورس تان | |

| درسي ڪتاب وڪي ڪتاب تان | |

- Geography at the Encyclopaedia Britannica website

- Definition of geography at Dictionary.com

- Definition of geography by Lexico

- Origin and meaning of geography by Online Etymology Dictionary

- Topic Dictionaries at Oxford Learner's Dictionaries

حوالا

[سنواريو]- ↑ "Areography". Merriam-Webster. حاصل ڪيل 27 July 2022.

- ↑ Lowell, Percival (April 1902). "Areography". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 41 (170): 225–234. https://www.jstor.org/stable/983554. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ↑ Sheehan, William (19 September 2014). "Geography of Mars, or Areography". Camille Flammarion's the Planet Mars. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. 409. pp. 435–441. doi:. ISBN 978-3-319-09640-7.

- ↑ Hayes-Bohanan, James. "What is Environmental Geography, Anyway?". webhost.bridgew.edu. Bridgewater State University. وقت 26 October 2006 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Hornby, William F.; Jones, Melvyn (29 June 1991). An introduction to Settlement Geography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28263-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=DLpzQgAACAAJ.

- ↑ Hughes, William. (1863). The Study of Geography. Lecture delivered at King's College, London, by Sir Marc Alexander. Quoted in Baker, J.N.L (1963). The History of Geography. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-85328-022-4.

- ↑ Hough, Carole; Izdebska, Daria (2016). "Names and Geography". in Gammeltoft, Peder. The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965643-1.

- ↑ Hough, Carole; Izdebska, Daria (2016). "Names and Geography". in Gammeltoft, Peder. The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965643-1.

- ↑ Cotterill, Peter D. "What is geography?". AAG Career Guide: Jobs in Geography and related Geographical Sciences. American Association of Geographers. وقت 6 October 2006 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 9 October 2006.

- ↑ Hayes-Bohanan, James. "What is Environmental Geography, Anyway?". webhost.bridgew.edu. Bridgewater State University. وقت 26 October 2006 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Haidu, Ionel (2016). "What is Technical Geography". Geographia Technica 11 (1): 1–5. doi:. https://technicalgeography.org/pdf/1_2016/01_haidu.pdf. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ Clifford, Nicholas J.; Holloway, Sarah L.; Rice, Stephen P. et al., eds (2014). Key Concepts in Geography (2nd ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-3022-2. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/key-concepts-in-geography/book230446. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ↑ Holloway, Sarah L.; Rice, Stephen P.; Valentine, Gill, eds (2003). Key Concepts in Geography (1st ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-0761973898.

- ↑ Clifford, Nicholas J.; Holloway, Sarah L.; Rice, Stephen P. et al., eds (2014). Key Concepts in Geography (2nd ed.). Sage. ISBN 978-1-4129-3022-2. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/key-concepts-in-geography/book230446. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ↑ Guidelines for Geographic Education: Elementary and Secondary Schools. The Council. 1984. ISBN 9780892911851.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Natoli, Salvatore J. (1 January 1994). "Guidelines for Geographic Education and the Fundamental Themes in Geography". Journal of Geography 93 (1): 2–6. doi:. ISSN 0022-1341. Bibcode: 1994JGeog..93....2N. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00221349408979676.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Buchanan, Lisa Brown; Tschida, Christina M. (2015). "Exploring the five themes of geography using technology". The Ohio Social Studies Review 52 (1): 29–39. https://ossr.scholasticahq.com/api/v1/attachments/2781/download.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Chapter 3: Geography's Perspectives". Rediscovering Geography: New Relevance for Science and Society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 1997. p. 28. doi:. ISBN 978-0-309-05199-6. http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=4913&page=28. Retrieved 2014-05-06.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Matthews, John; Herbert, David (2008). Geography: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921128-9.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Thrift, Nigel (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Space, The Fundamental Stuff of Geography (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ Kent, Martin (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Space, Making Room for Space in Physical Geography (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 97–119. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Tuan, Yi-Fu (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3877-2.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Chen, Xiang; Clark, Jill (2013). "Interactive three-dimensional geovisualization of space-time access to food". Applied Geography 43: 81–86. doi:. Bibcode: 2013AppGe..43...81C. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0143622813001367. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ↑ Tuan, Yi-Fu (1991). "Language and the Making of Place: A Narrative-Descriptive Approach". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81 (4): 684–696. doi:.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Tuan, Yi-Fu (1991). "A View of Geography". Geographical Review 81 (1): 99–107. doi:. Bibcode: 1991GeoRv..81...99T. https://www.jstor.org/stable/215179. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Castree, Noel (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, Connections and Boundaries in an Interdependent World (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Gregory, Ken (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, The Management of Sustainable Physical Environments (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 173–199. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Tobler, Waldo (1970). "A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region". Economic Geography 46: 234–240. doi:. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/eaa5/eefedd4fa34b7de7448c0c8e0822e9fdf956.pdf. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Tobler, Waldo (2004). "On the First Law of Geography: A Reply". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94 (2): 304–310. doi:. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Thrift, Nigel (1977). An Introduction to Time-Geography. Geo Abstracts, University of East Anglia. ISBN 0-90224667-4.

- ↑ Thornes, John (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Time, Change and Stability in Environmental Systems (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 119–139. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ Taylor, Peter (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Time, From Hegemonic Change to Everyday life (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 140–152. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ Galison, Peter Louis (1979). "Minkowski's space–time: From visual thinking to the absolute world". Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 10: 85–121. doi:.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Miller, Harvey (2017). "Time geography and space–time prism". International Encyclopedia of Geography: People, the Earth, Environment and Technology: 1–19. doi:. ISBN 978-0470659632. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0431. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ↑ Monmonier, Mark (1990). "Strategies For The Visualization Of Geographic Time-Series Data". Cartographica 27 (1): 30–45. doi:. https://utpjournals.press/doi/10.3138/U558-H737-6577-8U31. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ↑ حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBurt - ↑ 37.0 37.1 Herod, Andrew (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Scale, the local and the global (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Arbia, Giuseppe; Benedetti, R.; Espa, G. (1996). ""Effects of MAUP on image classification"". Journal of Geographical Systems 3: 123–141.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Smith, Peter (2005). "The laws of geography". Teaching Geography 30 (3): 150. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23756334.

- ↑ DeLyser, Dydia; Herbert, Steve; Aitken, Stuart; Crang, Mike; McDowell, Linda (November 2009). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Geography (1 ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412919913. https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/the-sage-handbook-of-qualitative-geography/book228796#preview. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ↑ Yano, Keiji (2001). "GIS and quantitative geography". GeoJournal 52 (3): 173–180. doi:.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Walker, Robert Toovey (28 April 2021). "Geography, Von Thünen, and Tobler's first law: Tracing the evolution of a concept". Geographical Review 112 (4): 591–607. doi:.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 Tobler, Waldo (2004). "On the First Law of Geography: A Reply". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94 (2): 304–310. doi:. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 Goodchild, Michael (2004). "The Validity and Usefulness of Laws in Geographic Information Science and Geography". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94 (2): 300–303. doi:.

- ↑ Tobler, Waldo (1999). "Linear pycnophylactic reallocation comment on a paper by D. Martin". International Journal of Geographical Information Science 13 (1): 85–90. doi:. Bibcode: 1999IJGIS..13...85T.

- ↑ Hecht, Brent; Moxley, Emily (2009). "Terabytes of Tobler: Evaluating the First Law in a Massive, Domain-Neutral Representation of World Knowledge". Spatial Information Theory. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 5756. Springer. p. 88. doi:. ISBN 978-3-642-03831-0. Bibcode: 2009LNCS.5756...88H.

- ↑ Otto, Philipp; Dogan, Osman; Taspınar, Suleyman, "A Dynamic Spatiotemporal Stochastic Volatility Model with an Application to Environmental Risks", Econometrics and Statistics, arXiv:2211.03178, doi:10.1016/j.ecosta.2023.11.002 Unknown parameter

|s2cid=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Zou, Muquan; Wang, Lizhen; Wu, Ping; Tran, Vanha (23 July 2022). "Mining Type-β Co-Location Patterns on Closeness Centrality in Spatial Data Sets". ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 11 (8): 418. doi:. Bibcode: 2022IJGI...11..418Z.

- ↑ Zhang, Yu; Sheng, Wu; Zhao, Zhiyuan; Yang, Xiping; Fang, Zhixiang (30 January 2023). "An urban crowd flow model integrating geographic characteristics". Scientific Reports 13 (1): 1695. doi:. PMID 36717687. Bibcode: 2023NatSR..13.1695Z.

- ↑ Heffernan, Mike (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Histories of Geography (2nd ed.). Sage. pp. 3–20. ISBN 978-1-4129-3022-2.

- ↑ Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Talbert, Richard J.A. (2009). Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ Siebold, Jim. "Babylonian clay tablet, 600 B.C.". henry-davis.com. Henry Davis Consulting Inc. وقت 9 November 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Delano Smith, Catherine (1996). "Imago Mundi's Logo the Babylonian Map of the World". Imago Mundi 48: 209–211. doi:.

- ↑ Finkel, Irving (1995). A join to the map of the world: A notable discovery. British Museum Magazine. ISBN 978-0-7141-2073-7.

- ↑ Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Talbert, Richard J.A. (2009). Geography and Ethnography: Perceptions of the World in Pre-Modern Societies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ↑ Kish, George (1978). A Source Book in Geography. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-82270-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=_6qF4vjZvhYC. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ Kish, George (1978). A Source Book in Geography. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-82270-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=_6qF4vjZvhYC. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ Tassoul, Jean-Louis; Tassoul, Monique (2004). A Concise History of Solar and Stellar Physics. London: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11711-9. https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof00tass.

- ↑ Smith, Sir William (1846). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology: Earinus-Nyx. 2nd. London: Taylor and Walton. https://books.google.com/books?id=AvcGAAAAQAAJ. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ Sullivan, Dan. "Mapmaking and its History". rutgers.edu. Rutgers University. وقت 4 March 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Needham, Joseph (1959). Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1959). Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. 3. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC.

- ↑ Nawwab, Ismail I.; Hoye, Paul F.; Speers, Peter C. "Islam and Islamic History and The Middle East". islamicity.com. وقت 17 June 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Edson, Evelyn; Savage-Smith, Emilie (2007). "Medieval Views of the Cosmos". International Journal of the Classical Tradition 13 (3): 61–63.

- ↑ Tibbetts, Gerald R. (1997). "The Beginnings of a Cartographic Tradition". in Harley, John Brian. The history of cartography. 2. Chicago: Brill. ISBN 0-226-31633-5. https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V2_B1/Volume2_Book1.html. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ King, David A. (1996). Rashed, Roshdi. ed. Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, genomics and timekeeping. 1. ISBN 978-0-203-71184-2. http://qisar.fssr.uns.ac.id/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Qisar-Roshdi-Rashed-Encyclopedia-of-the-History-of-Arabic-Science.pdf.

- ↑ Aber, James Sandusky. "Abu Rayhan al-Biruni". academic.emporia.edu. Emporia State University. وقت 11 August 2011 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Goodman, Lenn Evan (1992). Avicenna. Great Britain: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-01929-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=VJ6x-pcqMicC. Retrieved 3 May 2020. "It was Biruni, not Avicenna, who found a way for a single man, at a single moment, to measure the earth's circumference, by trigonometric calculations based on angles measured from a mountaintop and the plain beneath it – thus improving on Eratosthenes' method of sighting the sun simultaneously from two different sites, applied in the ninth century by astronomers of the Khalif al-Ma'mun."

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Baker, J. N. L. (1955). "The Geography of Bernhard Varenius". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) 21 (21): 51–60. doi:.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Warntz, William (1989). "Newton, the Newtonians, and the Geographia Generalis Varenii". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 79 (2): 165–191. doi:. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2563251. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ↑ Aber, James Sandusky. "Abu Rayhan al-Biruni". academic.emporia.edu. Emporia State University. وقت 11 August 2011 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Livingstone, David N.; Withers, Charles W. J. (2011-07-15). Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-226-48726-7.

- ↑ Société de Géographie. "Société de Géographie, Paris, France". socgeo.com (ٻولي ۾ French). Société de Géographie. وقت 6 November 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "About Us". rgs.org. Royal Geographical Society. وقت 18 October 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Русское Географическое Общество (основано в 1845 г.)". rgo.ru (ٻولي ۾ Russian). Russian Geographical Society. وقت 24 May 2012 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "History". amergeog.org. The American Geographical Society. وقت 17 October 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "National Geographic Society". state.gov. U.S. Department of State. وقت 23 December 2019 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Hartshorne, Richard (1939). "The pre-classical period of modern geography". Annals of the Association of American Geographers 29 (3): 35–48. doi:. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00045603909357282.

- ↑ Kerski, Joseph J. (2016). Interpreting Our World: 100 Discoveries That Revolutionized Geography. ABC-Clio. pp. 284. ISBN 9781610699204.

حوالي جي چڪ: "Note" نالي جي حوالن جي لاءِ ٽيگ <ref> آهن، پر لاڳاپيل ٽيگ <references group="Note"/> نہ مليو