يوڪيريئوٽا

| يوڪيريئوٽس Temporal range: اوروسيريئن -اڃان تائين موجود - سانچو:ھڪ ڊگھي دؤر وارو پنڊپھڻ | |

|---|---|

| |

| يوڪيريئوٽس ء ان جي قسمن جا مثال- ڪلاڪ وائيز مٿان کان کاٻي پاسي: ڳاڙھي رازي ماکي جي مک، بوليٽس ايڊيولس، چمپنيزي، آئسوٽرائيڪا انٽيسٽنلس، فارسي مکڻو ڪوپ ۽ والواڪس ڪارٽيري | |

| سائنسي درجا بندي | |

| Unrecognized taxon (fix): | يوڪيريئوٽا |

| ڪنگڊمز آف يوڪيريئوٽا[2] يا سپر گروپ | |

يوڪيريئوٽڪ جاندارن مان جيڪي جانورن، ٻوٽن ۽ فنگيا جي ڪنگڊمن يا تقسيمن ۾ شامل ڪري سگھڻ جھڙا نہ ھوندا آھن تہ کين پروٽيسٽا جي ڪنگڊم م رکيو ويندو آهي. | |

يوڪيريئوٽس (Eukaryotes) اھڙن جاندارن جو نالو آھي جنھن جي گھرڙي کي جھلي ۾ ويڙھيل مرڪز (cell nucleus) ھوندو آھي. جڏھن تہ بئڪٽيريا ۽ آرڪائيا کي مرڪز ڪانہ ٿيندو آهي.[3] [4][5] يوڪيريئوٽس جو تعلق يوڪيريئوٽا يا يوڪيريا سان آھي. لفظ يوڪيريئوٽا يوناني ٻوليءَ جي ٻن لفظن؛ "εὖ" (یو: معني، چڱو يا سچو) ء "κάρυον" (ڪيريون، معني گورو)، مان نڪتل آهي.

يوڪيريئوٽڪ جاندارن جي گھرڙن جا عضو جھلي ۾ ویڙھيل ھوندا آھن. ڪجهه ٻوٽن ۽ الجائي جي گھرڙن ۾ ڪلوروپلاسٽ پڻ ھوندو آھي. انھن جي جھلي دار نظام کي اينڊو ميمبرين سڏيو ويندو آهي.[6] گھرڙن جو مرڪز ٻٽي جھلي ۾ ويڙھيل ھوندو آھي جنھن کي نيوڪليئس ميمبرين يا نيوڪليئس جو لفافو بہ چوندا آھن جنھن ۾ سنھا سوراخ ھوندا آھن جن ذريعي مادا اندر داخل يا خارج ٿيندا آهن.[7] اھي بناوٽ جون خاصيتون ھڪ گھرڙيائي جاندارن، آرڪيئا ء بئڪٽيريا ۾ نہ ھونديون آھن. يوڪيريئوٽس گھڻ گھرڙيائي جاندار ھوندا آھن ۽ انھن جا گھرڙا پاڻ ۾ ملي مختلف نمونن جا تاندورا (tissue) ٺاھيندا آھن. ھڪ گھرڙيائي يوڪيريئوٽس کي پروٽسٽس (protists) سڏيو ويندو آهي. جانور ۽ ٻوٽا سڀ کان وڌيڪَ سڃاتل يوڪيريئوٽس آھن. يوڪيريئوٽس جاندارن م پيدائش جو ھڪ طريقو جنسي ميلاپ وارو، ميئوسس (meiosis) هوندو آهي، جنھن ۾ ھڪ گھرڙو ورھائجي ٻن ھڪ جھڙن جينياتي بناوٽ وارن گھرڙن ۾ تبديل ٿي ويندا آهن. پيدائش جو ٻيو طريقو وري جنسي ميلاپ کان سواءِ ٿيندو آهي جنھن کي "مٽوسس" (mitosis) چوندا آهن جنھن م ڊي اين اي جو پيدائشي عمل (DNA replication) گھرڙي جي تقسيم جي ٻن ڦيرن سان چار ھیپلائڊ (haploid daughter cells) پيدا ڪندا آهن جيڪي جنسي گھرڙن يا گئميٽ (gamete) وارو ڪم ڪندا آھن. انھن مان ھر گئميٽ ۾ ڪروموسومز جو ھڪ سيٽ ھوندو آھي.[8] دنيا جي ننڍن جاندارن جو سڀ برادريون ھن حياتي دائري سان تعلق رکن ٿيون.[9] يوڪيريئوٽا جاندارن جي شروعات 1.6 ارب سال کان 2.1 ارب سالن واري دؤر ۾ ٿي، جن کي پروٽيروزوئڪ دؤر (Proterozoic eon) جي نالي سان سڃاتو وڃي ٿو.

مٽوڪونڊرين (Mitochondrion) جملي سڀني يوڪيريئوٽا، سواءِ ھڪ قسم جي، جي گھرڙن جو ھڪ ننڍڙو جزو يا عضو آھي. رڳو ھڪ يوڪيريئوٽا، مونوسيرڪامنائڊ اھو عضو وڃائي ڇڏيو آهي.[10] مٽوڪونڊريا گھرڙي اندر کنڊ کي ايڊينوسائن ٽراء فاسفيٽ (ATP) ۾ تبديل ڪري يوڪيريئوٽڪ گھرڙي کي توانائي فراھم ڪندو آهي.[11] مٽوڪونڊريا ۾ پنھنجو الڳ قسم جو ڊي اين اي (DNA) ٿئي ٿو جيڪو بناوٽ ۾ بئڪٽيريا جي ڊي اين اي وانگر ھوندو آھي جيڪو rRNA ۽ tRNA جينز کي پنھنجي ضابطي ۾ رکندو آهي ۽ آر اين اي (RNA) کي پيدا ڪندو آھي، جنھن جي مشابهت يوڪيريئوٽا جي ڀيٽ ۾ بئڪٽيريا جي آر اين اي سان وڌيڪ ھوندي آھي.[12]

تاريخ

[سنواريو]

يوڪيريئوٽا وارو خيال ھڪ فرينچ حياتياتي ماھر، ايڊورڊ چئٽن (Edouard Chatton؛ 1883-1947) سان منصوب ڪيو ويندو آهي. لفظ پروڪيريئوٽ (prokaryote) ۽ يوڪيريئوٽ (eukaryote) وري ڪيناڊا جي حياتياتي ماھر، راجر اسٽينيئر ۽ آمريڪا جي ڊچ نسل واري مائڪروبائيولاجي جي ماھر، سي.بي.وان نيل (C.B. van Niel) سال 1962ع ۾ ٻيھر متعارف ڪرايا.

تنوع

[سنواريو]يوڪريوٽ جاندار جيڪي خوردبيني سنگل-سيلولر, 3 مائڪرو ميٽرن کان هيٺ پکين کان وٺي، بليو وهيل جهڙا جانور، جن جو وزن 190 ٽين تائين ۽ ماپ 33.6 ميٽر (110 فوٽ) ڊگهو آهي، يا ٻوٽا جهڙوڪ ساحل ريڊ ووڊ، 120 ميٽر (390 فوٽ) کان مٿي ڊگهو، هوندا آهن آهي. ڪيترائي يوڪريوٽ سنگل-سيلولر آهن؛ غير رسمي گروهه جنهن کي پروٽسٽ سڏيو ويندو آهي، انهن مان، ڪجهه گهڻ-سيلولر شڪل آهن جهڙوڪ 200 فوٽ (61 ميٽر) ڊگهو Kellop, تائين شامل آهن. گھڻ-سيلولر يوڪريوٽس ۾ جانور، ٻوٽا ۽ فنگس شامل آهن، پر ٻيهر، انهن گروپن ۾ پڻ ڪيترائي يونيسيلولر نسل شامل آهن. يوڪريوٽڪ سيل عام طور تي پروڪاريوٽس ; بيڪٽيريا ۽ آرڪيا; جي ڀيٽ ۾ تمام وڏا هوندا آهن جن جو حجم تقريباً 10,000 ڀيرا وڌيڪ هوندو آهي. يوڪريوٽس جاندارن جي تعداد جي هڪ ننڍڙي اقليت جي نمائندگي ڪن ٿا، پر جيئن ته انهن مان گهڻا وڏا آهن. يوڪريوٽ سائز ۾ سنگل سيل کان وٺي ڪيترن ئي ٽن وزني جاندارن تائين گهڻا وڏا آهن. انهن جو مجموعي عالمي بايوماس (468 گيگاٽن) پروڪاريوٽس (77 گيگاٽن) کان تمام گهڻو وڏو آهي، جنهن ۾ رڳو ٻوٽا ڌرتيء جي ڪل بايوماس جا 81 سيڪڙو کان وڌيڪ آهن.

Eukaryotes are organisms that range from microscopic single cells, such as picozoans under 3 micrometres across,[13] to animals like the blue whale, weighing up to 190 tonnes and measuring up to 33.6 ميٽر (110 ft) long,[14] or plants like the coast redwood, up to 120 ميٽر (390 ft) tall.[15] Many eukaryotes are unicellular; the informal grouping called protists includes many of these, with some multicellular forms like the giant kelp up to 200 فٽ (61 m) long.[16] The multicellular eukaryotes include the animals, plants, and fungi, but again, these groups too contain many unicellular species.[17] Eukaryotic cells are typically much larger than those of prokaryotes—the bacteria and the archaea—having a volume of around 10,000 times greater.[18][19] Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, as many of them are much larger, their collective global biomass (468 gigatons) is far larger than that of prokaryotes (77 gigatons), with plants alone accounting for over 81% of the total biomass of Earth.[20]

- Eukaryotes range in size from single cells to organisms weighing many tons

-

پروڪريوٽ (هڪ ننڍڙي سيل وارو بيڪٽيريا - کاٻو جي) ۽ هڪ سيل وارو يوڪريوٽ پيراميشيم

-

ڪوسٽل ريڊ ووڊ

-

نيري وهيل

يوڪريوٽس هڪ متنوع نسب آهن، جن ۾ خاص طور تي خوردبيني جاندار آهن. ڪنهن نه ڪنهن شڪل ۾ گھڻ-سيلولر يوڪريوٽس جي اندر گهٽ ۾ گهٽ 25 ڀيرا آزاديءَ سان ترقي ڪئي آهي. ڪمپليڪس گھڻ-سيلولر جاندار، اموبيا جي مجموعي کي ڳڻڻ کان سواء سلم مولڊ ٺاهڻ لاء، صرف ڇهه يوڪريوٽڪ نسلن ۾ ترقي ڪئي آهي: جانور، سمبايوسس مايڪوٽن، فنگي، ناسي الجائي، ڳاڙهي الجائي، سائي الجائي ۽ زميني ٻوٽا. يوڪريوٽس جينوميڪ هڪجهڙائي جي لحاظ کان گروهه رکيا ويا آهن، تنهن ڪري اهي گروهه اڪثر ڪري نمايان گڏيل خاصيتون نه هوندا آهن.

eukaryotes are a diverse lineage, consisting mainly of microscopic organisms.[21] Multicellularity in some form has evolved independently at least 25 times within the eukaryotes.[22][23] Complex multicellular organisms, not counting the aggregation of amoebae to form slime molds, have evolved within only six eukaryotic lineages: animals, symbiomycotan fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and land plants.[24] Eukaryotes are grouped by genomic similarities, so that groups often lack visible shared characteristics.[21]

خاص خاصيتون

[سنواريو]نيوڪليئس

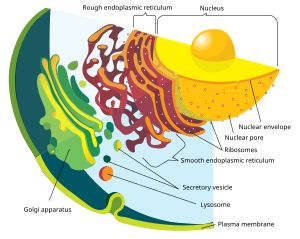

[سنواريو]يوڪريوٽ جي تعريف واري خصوصيت اها آهي ته انهن جي سيلن ۾ نيوڪليئس آهي. اھو انھن کي انھن جو يوناني نالو "εὖ" (يو، سٺو) ۽ "κάρυονn" (ڪريون، نٽ يا ڪرنيل، ھتي مطلب "نيوڪليس" آهي) ڏئي ٿو. يوڪريوٽڪ سيلن ۾ مختلف قسم جي اندروني جھلي سان جڙيل جوڙجڪ آهن، جن کي آرگنيلز سڏيو ويندو آهي ۽ هڪ سائٽوسڪيلٽن (cytoskeleton) جيڪو سيل جي جوڙجڪ ۽ شڪل کي بيان ڪري ٿو. نيوڪليئس سيل جي ڊي اين اي کي ذخيرو ڪري ٿو، جيڪو لڪيري بنڊلن ۾ ورهايل آهي جنهن کي ڪروموزوم سڏيو ويندو آهي؛ اهي ائٽمي تقسيم, خاص طور تي ميٽوسس (mitosis) جي يوڪريوٽڪ عمل جي دوران هڪ مائڪروٽيوبلر اسپنڊل ذريعي ٻن ملندڙ سيٽن ۾ ورهايل آهن.

، The defining feature of eukaryotes is that their cells have nuclei. This gives them their name, from the Greek εὖ (eu, "well" or "good") and κάρυον (karyon, "nut" or "kernel", here meaning "nucleus").[25] Eukaryotic cells have a variety of internal membrane-bound structures, called organelles, and a cytoskeleton which defines the cell's organization and shape. The nucleus stores the cell's DNA, which is divided into linear bundles called chromosomes;[26] these are separated into two matching sets by a microtubular spindle during nuclear division, in the distinctively eukaryotic process of mitosis.[27]

حياتياتي ڪيميا

[سنواريو]يوڪريوٽ ڪيترن ئي طريقن منفرد بايو ڪيميڪل رستن جهڙوڪ اسٽرين سنٿيسس سان پروڪاريوٽس کان مختلف آهن. يوڪريوٽڪ دستخطي پروٽين جو زندگيءَ جي ٻين شعبن ۾ موجود پروٽينن سان ڪو به هومولوجي نه آهي، پر يوڪريوٽس جي وچ ۾ عالمگير نظر اچي ٿو. انهن ۾ cytoskeleton جي پروٽين، پيچيده ٽرانسپشن مشينري، جھلي جي ترتيب ڏيڻ وارو نظام، ايٽمي سوراخ، ۽ بايو ڪيميڪل رستن ۾ ڪجهه اينزيمس شامل آهن.

differ from prokaryotes in multiple ways, with unique biochemical pathways such as sterane synthesis.[28] The eukaryotic signature proteins have no homology to proteins in other domains of life, but appear to be universal among eukaryotes. They include the proteins of the cytoskeleton, the complex transcription machinery, the membrane-sorting systems, the nuclear pore, and some enzymes in the biochemical pathways.[29]

اندروني جھلي

[سنواريو]Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, together forming the endomembrane system.[30] Simple compartments, called vesicles and vacuoles, can form by budding off other membranes. Many cells ingest food and other materials through a process of endocytosis, where the outer membrane invaginates and then pinches off to form a vesicle.[31] Some cell products can leave in a vesicle through exocytosis.[32]

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope, with nuclear pores that allow material to move in and out.[7] Various tube- and sheet-like extensions of the nuclear membrane form the endoplasmic reticulum, which is involved in protein transport and maturation. It includes the rough endoplasmic reticulum, covered in ribosomes which synthesize proteins; these enter the interior space or lumen. Subsequently, they generally enter vesicles, which bud off from the smooth endoplasmic reticulum.[33] In most eukaryotes, these protein-carrying vesicles are released and further modified in stacks of flattened vesicles (cisternae), the Golgi apparatus.[34]

Vesicles may be specialized; for instance, lysosomes contain digestive enzymes that break down biomolecules in the cytoplasm.[35]

Mitochondria

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Mitochondrion

Mitochondria are organelles in eukaryotic cells. The mitochondrion is commonly called "the powerhouse of the cell",[36] for its function providing energy by oxidising sugars or fats to produce the energy-storing molecule ATP.[37][38] Mitochondria have two surrounding membranes, each a phospholipid bilayer, the inner of which is folded into invaginations called cristae where aerobic respiration takes place.[39]

Mitochondria contain their own DNA, which has close structural similarities to bacterial DNA, from which it originated, and which encodes rRNA and tRNA genes that produce RNA which is closer in structure to bacterial RNA than to eukaryote RNA.[12]

Some eukaryotes, such as the metamonads Giardia and Trichomonas, and the amoebozoan Pelomyxa, appear to lack mitochondria, but all contain mitochondrion-derived organelles, like hydrogenosomes or mitosomes, having lost their mitochondria secondarily.[10] They obtain energy by enzymatic action in the cytoplasm.[40][10]

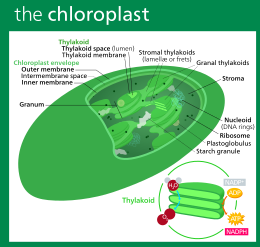

Plastids

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Plastid

Plants and various groups of algae have plastids as well as mitochondria. Plastids, like mitochondria, have their own DNA and are developed from endosymbionts, in this case cyanobacteria. They usually take the form of chloroplasts which, like cyanobacteria, contain chlorophyll and produce organic compounds (such as glucose) through photosynthesis. Others are involved in storing food. Although plastids probably had a single origin, not all plastid-containing groups are closely related. Instead, some eukaryotes have obtained them from others through secondary endosymbiosis or ingestion.[41] The capture and sequestering of photosynthetic cells and chloroplasts, kleptoplasty, occurs in many types of modern eukaryotic organisms.[42][43]

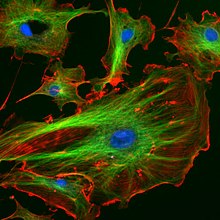

Cytoskeletal structures

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton provides stiffening structure and points of attachment for motor structures that enable the cell to move, change shape, or transport materials. The motor structures are microfilaments of actin and actin-binding proteins, including α-actinin, fimbrin, and filamin are present in submembranous cortical layers and bundles. Motor proteins of microtubules, dynein and kinesin, and myosin of actin filaments, provide dynamic character of the network.[44][45]

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or multiple shorter structures called cilia. These organelles are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin, and are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagella. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella may have hairs (mastigonemes), as in many Stramenopiles. Their interior is continuous with the cell's cytoplasm.[46][47]

Centrioles are often present, even in cells and groups that do not have flagella, but conifers and flowering plants have neither. They generally occur in groups that give rise to various microtubular roots. These form a primary component of the cytoskeleton, and are often assembled over the course of several cell divisions, with one flagellum retained from the parent and the other derived from it. Centrioles produce the spindle during nuclear division.[48]

Cell wall

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Cell wall

The cells of plants, algae, fungi and most chromalveolates, but not animals, are surrounded by a cell wall. This is a layer outside the cell membrane, providing the cell with structural support, protection, and a filtering mechanism. The cell wall also prevents over-expansion when water enters the cell.[49]

The major polysaccharides making up the primary cell wall of land plants are cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. The cellulose microfibrils are linked together with hemicellulose, embedded in a pectin matrix. The most common hemicellulose in the primary cell wall is xyloglucan.[50]

جنسي پيدائش

[سنواريو]

يوڪريوٽس جي زندگي جو هڪ چڪر آهي جنهن ۾ جنسي پيدائش شامل آهي، هڪ هيپلوڊ مرحلي جي وچ ۾ متبادل، جتي هر هڪ ڪروموزوم جي صرف هڪ ڪاپي هر سيل ۾ موجود آهي، ۽ هڪ ڊپلوڊ مرحلو، هر سيل ۾ هر ڪروموزوم جون ٻه ڪاپيون آهن. ڊپلوميڊ مرحلو ٻن هيپلوڊ گيميٽس جي ميلاپ سان ٺهيو آهي، جهڙوڪ انڊا ۽ اسپرماتوزوا، هڪ زائگوٽ ٺاهڻ لاءِ؛ اهو هڪ جسم ۾ وڌي سگهي ٿو، ان جي سيلز کي ميٽوسس سان ورهائڻ سان، ۽ ڪجهه اسٽيج تي ميوسس ذريعي هيپلوڊ گيمٽس پيدا ڪري ٿو، هڪ تقسيم جيڪو ڪروموزوم جو تعداد گھٽائي ٿو ۽ جينياتي تبديلي پيدا ڪري ٿو.[51] هن نموني ۾ ڪافي فرق آهي. ٻوٽن ۾ هيپلوڊ ۽ ڊپلوڊ ملٽي سيلولر مرحلا آهن.[52] يوڪريوٽ ۾ ميٽابولڪ جي شرح گھٽ هوندي آهي ۽ پروڪاريوٽس جي ڀيٽ ۾ وڌيڪ پيدا ٿيڻ جو وقت هوندو آهي، ڇاڪاڻ ته اهي وڏا هوندا آهن ۽ ان ڪري انهن جي مٿاڇري واري ايراضي ۽ حجم جي نسبت ۾ ننڍي هوندي آهي.[53]

جنسي پيدائش جو ارتقا شايد يوڪريوٽس جي هڪ بنيادي خصوصيت ٿي سگهي ٿي. هڪ فيلوجينيٽڪ تجزيي جي بنياد تي، ڊيڪس ۽ راجر پيش ڪيو آهي ته فيڪلٽي جنس گروپ جي عام ابن ڏاڏن ۾ موجود هئي.[54] جين جو هڪ بنيادي سيٽ جيڪو ميوسس ۾ ڪم ڪري ٿو، ٽريچوموناس واگيناليس ۽ گيارڊيا انٽيسٽنيلس، ٻه جاندار جيڪي اڳ ۾ غير جنسي سمجهيا ويندا هئا، ٻنهي ۾ موجود آهي.[55][56] ڇاڪاڻ ته اهي ٻئي نسلون هن نسلن مان آهن جيڪي ابتدائي طور تي يوڪريوٽڪ ارتقائي وڻ کان ڌار ٿي ويون آهن، بنيادي مييوٽڪ جين، ۽ ان ڪري جنس، ممڪن آهي ته يوڪريوٽس جي عام ابن ڏاڏن ۾ موجود هئا.[55][56] نسلن کي هڪ ڀيرو غير جنسي سمجهيو ويندو هيو، جهڙوڪ لشمانيا پرازي، هڪ جنسي چڪر رکندو آهي.[57] اموايبائي (Amoebae)، اڳ ۾ غير جنسي سمجهيو ويندو هو، شايد قديم طور تي جنسي هجي. جڏهن ته هاڻوڪي غير جنسي گروهه ٿي سگهي ٿو تازو پيدا ٿيا آهن.[58]

ارتقا

[سنواريو]

درجه بندي جي تاريخ

[سنواريو]آڳاٽي دور ۾، جانورن ۽ ٻوٽن جي ٻن سلسلن کي ارسطو ۽ ٿيو فراسٽس تسليم ڪيو هو. 18هين صدي عيسوي ۾ لينئي پاران هنن کي ڪنگڊم جو درجو ڏنو ويو. جيتوڻيڪ هن فنگس کي ٻوٽن سان گڏ ڪجهه تحفظات سان شامل ڪيو، بعد ۾ اهو محسوس ڪيو ويو ته اها بلڪل الڳ آهن ۽ هڪ الڳ ڪنگڊم جي ضمانت ڏين ٿا.[60] مختلف هڪ- گھرڙن وارا يوڪريوٽس اصل ۾ ٻوٽن يا جانورن سان گڏ رکيا ويا هئا جڏهن اهي سڃاتل ٿي ويا. سال 1818ع ۾ جرمن بايولوجسٽ، جارج اي گولڊ فُس لفظ "پروٽوزوآ" (protozoa) جوڙايو ته جيئن جاندار جهڙوڪ سيليئٽس (ciliates) ڏانهن اشارو ڪيو وڃي[61] ۽ هن گروهه کي ان وقت تائين وڌايو ويو، جيستائين ارنسٽ هيڪل ان کي هڪ ڪنگڊم بنايو، جنهن ۾ 1866ع ۾ سڀني هڪ جيو گھرڙي وارا يوڪريوٽس يعني پروٽيسٽا شامل ٿي ويا.[62][63][64] هن طرح يوڪئريوٽس کي چار ڪنگڊم جي طور تي ڏٺو ويو:

- ڪنگڊم پروٽسٽا

- ڪنگڊم پلانٽائي

- ڪنگڊم فنگائي

- ڪنگڊم انيماليا

پروٽسٽ ان وقت ”ابتدائي شڪل“ سمجهيا ويندا هئا، ۽ اهڙيءَ طرح هڪ ارتقائي درجو، انهن جي ابتدائي هڪ-گھرڙيائي فطرت سان متحد ٿي ويا.[65] زندگيءَ جي وڻ ۾ سڀ کان پراڻي شاخن جي سمجھاڻي صرف ڊي اين اي جي ترتيب سان ڪافي ترقي ڪئي، جنهن جي ڪري ڪنگڊم جي بجاءِ ڊومينز جو هڪ سرشتو پيدا ٿيو جيئن 1990ع ۾ ڪارل ويز، اوٽو ڪنڊلر ۽ مارڪ ويلس پاران مٿين سطح جو درجو پيش ڪيو ويو، سڀني يوڪريوٽ کي متحد ڪري. ڊومين ۾ ڪنگڊم "يوڪاريا" بيان ڪندي، جيتوڻيڪ، يوڪريوٽس قابل قبول عام مترادف جاري رهيو.[66][67] سال 1996ع ۾، ارتقائي حياتيات جي ماهر، لين مارگوليس تجويز ڏنو ته ڪنگڊم ۽ ڊومينز جي بجاء شامل نالن سان سمبوسس جي بنياد تي فائلوجيني ٺاهي، "يوڪاريا" جو وضاحت ڪيو.[68]

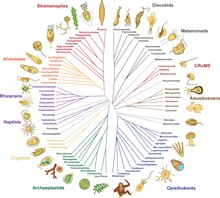

فائلوجيني

[سنواريو]

سال 2014ع تائين، گذريل ٻن ڏهاڪن جي فائلوجينومڪ مطالعي مان ھڪڙي اتفاق راءِ پيدا ٿيڻ شروع ٿي.[17][69] يوڪريوٽس جي اڪثريت کي ٻن وڏين ڪلئڊن مان ھڪڙي ۾ رکي سگھجي ٿو جنھن کي "امورفيا" (Amorphea) سڏيو ويندو آھي (جيڪو ٺھيل ۾ يونيڪونٽ مفروضو آھي) ۽ ڊائي ڦوڊا (Diphoda) (اڳوڻو بائيڪونٽ)، جنھن ۾ ٻوٽا ۽ سڀ کان وڌيڪ الجائي (algal) نسب شامل آھن. هڪ ٽيون وڏو گروهه، ايڪسڪاوئٽا، هڪ رسمي گروپ جي طور تي ڇڏي ڏنو ويو آهي ڇاڪاڻ ته اهو طفيلي (paraphyletic) آهي.[70] هيٺ ڏنل تجويز ڪيل فائلوجيني صرف هڪ گروپ، ڊسڪوبا (Discoba) جي کوٽائي شامل آهي[71] ۽ 2021ع جي تجويز کي شامل ڪري ٿو ته پڪوزوئن روڊوفائٽس جا ويجها مائٽ آهن. [72] پرووورا سال 2022ع ۾ دريافت ڪيل مائڪروبيل حملا آورن (predators) جو هڪ گروپ آهي.[73]

يوڪاريوٽس جي ابتدا

[سنواريو]

- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو يوڪاريوجينيسس

يوڪريوٽڪ سيل جي ابتدا، يا يوڪاريوجينيسس، زندگيءَ جي ارتقا ۾ هڪ سنگ ميل آهي، ڇاڪاڻ ته يوڪريوٽس ۾ سڀ پيچيده سيل ۽ لڳ ڀڳ سڀ ملٽي سيلولر جاندار شامل آهن. آخري يوڪريوٽڪ عام اباڻي (LECA) سڀني جاندار يوڪريوٽس جي فرضي اصليت آهي[75] ۽ گهڻو ڪري، هڪ فرد نه، هڪ حياتياتي آبادي هئي.[76] آخري يوڪريوٽڪ عام اباڻي (LECA) کي مڃيو وڃي ٿو ته هڪ نيوڪليس, گهٽ ۾ گهٽ هڪ سينٽريول ۽ فليگيلم، بنيادي طور تي ايروبڪ ميڪوڪونڊريا، جنس (مييوسس ۽ سنگامي)، هڪ غير فعال سسٽ جنهن ۾ چيٽين يا سيلولوز جي سيل وال سان گڏ ۽ پيروڪسيسوم سان، هڪ پروٽسٽ آهي.[77][78][79]

متحرڪ anaerobic archaean ۽ aerobic alphaproteobacterium جي وچ ۾ هڪ endosymbiotic اتحاد LECA ۽ سڀني eukaryotes کي جنم ڏنو، mitochondria سان. هڪ سيڪنڊ، گهڻو پوءِ هڪ سائانو بيڪٽيريا سان Endosymbiosis ٻوٽن جي اباڻي کي جنم ڏنو، ڪلوروپلاسٽس سان. آرڪيا ۾ يوڪريوٽڪ بائيو مارڪرز جي موجودگي آثار قديمه ڏانهن اشارو ڪري ٿي. Asgard archaea جي جينومس ۾ ڪافي مقدار ۾ Eukaryotic signature پروٽين جين موجود آهن، جيڪي cytoskeleton جي ترقي ۾ اهم ڪردار ادا ڪن ٿا ۽ eukaryotes جي پيچيده سيلولر ڍانچي جي خاصيت. 2022 ۾، cryo-electron tomography ظاھر ڪيو ته Asgard archaea ۾ ھڪڙو پيچيده ايڪٽين تي ٻڌل سائٽوسڪليٽن آھي، جيڪو يوڪريوٽس جي قديم آثارن جو پھريون سڌو سنئون ثبوت مهيا ڪري ٿو.

An endosymbiotic union between a motile anaerobic archaean and an aerobic alphaproteobacterium gave rise to the LECA and all eukaryotes, with mitochondria. A second, much later endosymbiosis with a cyanobacterium gave rise to the ancestor of plants, with chloroplasts.[80]

The presence of eukaryotic biomarkers in archaea points towards an archaeal origin. The genomes of Asgard archaea have plenty of Eukaryotic signature protein genes, which play a crucial role in the development of the cytoskeleton and complex cellular structures characteristic of eukaryotes. In 2022, cryo-electron tomography demonstrated that Asgard archaea have a complex actin-based cytoskeleton, providing the first direct visual evidence of the archaeal ancestry of eukaryotes.[81]

فوسل

[سنواريو]يوڪريوٽ جي اصليت جو وقت معلوم ڪرڻ ڏکيو آهي، پر ڪنگشانيا ميگنيفيسيا (Qingshania magnificia) جي دريافت، اتر چين مان سڀ کان قديم ملٽي سيلولر يوڪريوٽ، جيڪو 1.635 بلين سال اڳ جي دور ۾ رهندو هو، اهو ظاهر ڪري ٿو ته تاج گروپ يوڪريوٽس پيلوپروٽيروزوڪ (اسٽيرين) دور مان پيدا ٿيو هوندو. سڀ کان اوائلي غير واضح يونيسيلولر يوڪريوٽس جيڪي لڳ ڀڳ 1.65 بلين سال اڳ جي دور ۾ رهندا هئا. اهي پڻ اتر چين مان دريافت ڪيا ويا آهن: تپانيا پلانا, شيوسپاريڊم ميڪروريٽيڪولاٽم, ڊڪٽواسفيرا ميڪروريٽيڪولاٽا، جيڪو

Germino. sphaera alveo. لتا ۽ والريا لوفو. اسٽريٽا ڪجھ ايڪريارچ گهٽ ۾ گهٽ 1.65 بلين سال اڳ کان سڃاتا وڃن ٿا، ۽ هڪ فوسل، گريپينيا، جيڪو شايد هڪ الگا هجي، جيترو 2.1 بلين سال پراڻو آهي. "مسئلو" فوسل ڊسڪاگما 2.2 بلين سال پراڻي paleosols ۾ مليو آهي.

the earliest unequivocal unicellular eukaryotes which lived during approximately 1.65 billion years ago are also discovered from North China: Tappania plana, Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum, Dictyosphaera macroreticulata, Germinosphaera alveolata, and Valeria lophostriata.[82]

Some acritarchs are known from at least 1.65 billion years ago, and a fossil, Grypania, which may be an alga, is as much as 2.1 billion years old.[83][84] The "problematic"[85] fossil Diskagma has been found in paleosols 2.2 billion years old.[85]

"وڏي نوآبادياتي جاندارن" جي نمائندگي ڪرڻ لاءِ تجويز ڪيل اڏاوتون (Palaeoproterozoic) جي ڪاري شيل ۾ مليون آهن جهڙوڪ فرانسويلين بي فارميشن، گبون ۾، "فرانسويلين بايوٽا" جو نالو ڏنو ويو آهي، جيڪو 2.1 بلين سال پراڻو آهي.[87] [88] بهرحال، انهن اڏاوتن جي حيثيت کي فوسلز جي حيثيت سان مقابلو ڪيو ويو آهي، ٻين ليکڪن سان گڏ اهو مشورو ڏئي ٿو ته اهي شايد (pseudofossils) جي نمائندگي ڪن ٿا. [89] سڀ کان پراڻا فوسلز غير واضح طور تي يوڪريوٽس کي تفويض ڪري سگهجن ٿا، چين جي روئيانگ گروپ مان آهن، جيڪي لڳ ڀڳ 1.8-1.6 بلين سال اڳ جي تاريخ جا آهن.[90] فوسلز جيڪي واضح طور تي جديد گروهن سان لاڳاپيل آهن هڪ اندازي مطابق 1.2 بلين سال اڳ، ڳاڙهي الجي جي صورت ۾ ظاهر ٿيڻ شروع ڪن ٿا، جيتوڻيڪ تازو ڪم ڏيکاري ٿو ته ونڌيا بيسن ۾ فوسيل ٿيل تنتي الجي جي وجود جي تاريخ شايد 1.6 کان 1.7 بلين سال اڳ واري هئي.[91]

آسٽريلين شيلز ۾ اسٽيرانن جي موجودگي، يوڪريوٽڪ-مخصوص بايو مارڪرز، اڳ ۾ اشارو ڪيو ويو آهي ته يوڪريوٽس انهن پٿرن ۾ موجود هئا جن جي تاريخ 2.7 بلين سال پراڻي هئي، [92] [93] پر اهي آرڪيائي بائيو مارڪرز کي بعد ۾ آلودگي جي طور تي رد ڪيو ويو آهي.[94] سڀ کان پراڻو صحيح بايو مارڪر رڪارڊ صرف 800 ملين سال پراڻو آهي. ان جي ابتڙ، هڪ ماليڪيولر ڪلاڪ جو تجزيو ڏيکاري ٿو ته اسٽيرول بايو سنٿيسس جي شروعات 2.3 بلين سال اڳ ٿي.[95] يوڪريوٽڪ بائيو مارڪرز جي طور تي اسٽيرانن جي فطرت ڪجهه بيڪٽيريا پاران اسٽيرولس جي پيداوار جي ڪري وڌيڪ پيچيدگي آهي.[96][97]

جڏهن ته انهن جي اصليت، يوڪريوٽس شايد گهڻي دير تائين ماحولياتي طور تي غالب نه ٿي سگهيا آهن؛ وڏي آباديءَ جي اڀار جي ڪري سامونڊي ٻوٽن جي زنڪ ٺهڻ ۾ وڏي پئماني تي اضافو ٿيو آهي.[98]

پڻ ڏسو

[سنواريو]خارجي لنڪس

[سنواريو]

- "Eukaryotes" آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 29 January 2012 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين. (Tree of Life Web Project)

حوالا

[سنواريو]- ↑ "Tracing back EFL gene evolution in the cryptomonads-haptophytes assemblage: separate origins of EFL genes in haptophytes, photosynthetic cryptomonads, and goniomonads". Gene 441 (1–2): 126–31. July 2009. doi:. PMID 18585873. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0378-1119(08)00219-9.

- ↑ "The revised classification of eukaryotes" (PDF). The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 59 (5): 429–93. September 2012. doi:. PMID 23020233. PMC 3483872. http://www.paru.cas.cz/docs/documents/93-Adl-JEM-2012.pdf. آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 16 December 2013 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين.

- ↑ Youngson, Robert M. (2006). Collins Dictionary of Human Biology. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-722134-7.

- ↑ Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ↑ Martin, E.A., ed (1983). Macmillan Dictionary of Life Sciences (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-333-34867-2.

- ↑ Linka, Marc; Weber, Andreas P.M. (2011). "Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells". Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. p. 215. ISBN 978-9400715332. https://books.google.com/books?id=WfzEgaLibuwC&pg=PA215.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The nuclear envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2 (3): a000539. March 2010. doi:. PMID 20300205. حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "TheNuclearEnvelope-NCBI" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Zimmer C. "Scientists Unveil New 'Tree of Life'". The New York Times. حاصل ڪيل 2016-04-11.

- ↑ "Prokaryotes: the unseen majority" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (12): 6578–83. June 1998. doi:. PMID 9618454. PMC 33863. Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.6578W. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/95/12/6578.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "A Eukaryote without a Mitochondrial Organelle". Current Biology 26 (10): 1274–1284. May 2016. doi:. PMID 27185558. حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Karn" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ "Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?". madsci.org.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Watson, James; Hopkins, Nancy; Roberts, Jeffery; Steitz, Joan Argetsinger; Weiner, Alan (1988). "28: The Origins of Life" (English ۾) (Hardcover). Molecular Biology of the Gene (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, CA: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc.. p. 1154. ISBN 0-8053-9614-4.

حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "MolecGene" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Seenivasan, Ramkumar; Sausen, Nicole; Medlin, Linda K.; Melkonian, Michael (26 March 2013). "Picomonas judraskeda Gen. Et Sp. Nov.: The First Identified Member of the Picozoa Phylum Nov., a Widespread Group of Picoeukaryotes, Formerly Known as 'Picobiliphytes'". PLOS ONE 8 (3): e59565. doi:. PMID 23555709. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...859565S.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9. https://archive.org/details/guinnessbookofan00wood.

- ↑ Earle CJ (وڪي نويس.). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. وقت 2016-04-01 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 2017-09-15. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30419-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=xuUoiFesSHMC. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 6 (5): a016147. May 2014. doi:. PMID 24789819.

- ↑ DeRennaux, B. (2001). "Eukaryotes, Origin of". Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2. Elsevier. pp. 329–332. doi:. ISBN 9780123847201.

- ↑ "Deep-sea microorganisms and the origin of the eukaryotic cell". Japanese Journal of Protozoology 47 (1,2): 29–48. 2014. http://protistology.jp/journal/jjp47/JJP47YAMAGUCHI.pdf.

- ↑ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (2018-05-17). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (25): 6506–6511. doi:. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 29784790. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.6506B.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBurki Roger Brown Simpson 2020 pp. 43–55 - ↑ Grosberg, RK; Strathmann, RR (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?". Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 38: 621–654. doi:. https://grosberglab.faculty.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/453/2017/05/2007-Grosberg-R.-K.-and-R.-R.-Strathmann.pdf. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ Parfrey, L.W.; Lahr, D.J.G. (2013). "Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes". BioEssays 35 (4): 339–347. doi:. PMID 23315654. http://www.producao.usp.br/bitstream/handle/BDPI/45022/339_ftp.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ↑ Popper, Zoë A.; Michel, Gurvan; Hervé, Cécile; Domozych, David S.; Willats, William G.T.; Tuohy, Maria G.; Kloareg, Bernard; Stengel, Dagmar B. (2011). "Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: From algae to flowering plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology 62: 567–590. doi:. PMID 21351878.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "eukaryotic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Bonev, B; Cavalli, G (14 October 2016). "Organization and function of the 3D genome". Nature Reviews Genetics 17 (11): 661–678. doi:. PMID 27739532.

- ↑ O'Connor, Clare. "Chromosome Segregation: The Role of Centromeres". Nature Education. حاصل ڪيل 18 February 2024.

eukar

- ↑ حوالي جي چڪ: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedsterane - ↑ "The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (3): 1420–5. February 2002. doi:. PMID 11805300. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.1420H.

- ↑ "Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells". Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. 2011. p. 215. ISBN 978-94-007-1533-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=WfzEgaLibuwC&pg=PA215. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Endocytosis. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-963851-2.

- ↑ Stalder, Danièle; Gershlick, David C. (November 2020). "Direct trafficking pathways from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 107: 112–125. doi:. PMID 32317144.

- ↑ "Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)". British Society for Cell Biology. وقت 24 March 2019 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 12 November 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Golgi Apparatus". British Society for Cell Biology. وقت 13 November 2017 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 12 November 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Lysosome". British Society for Cell Biology. وقت 13 November 2017 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 12 November 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation 10 (1): 131–144. July 1957. doi:. PMID 32166015. Bibcode: 1957SciAm.197a.131S.

- ↑ Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. 2006. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 978-0471214953. https://archive.org/details/fundamentalsofbi00voet_0/page/547.

- ↑ Mack S. "Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?". madsci.org. وقت 24 April 2014 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 24 April 2014. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Zick, M; Rabl, R; Reichert, AS (January 2009). "Cristae formation-linking ultrastructure and function of mitochondria.". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1793 (1): 5–19. doi:. PMID 18620004.

- ↑ Davis JL. "Scientists Shocked To Discover Eukaryote With NO Mitochondria". IFL Science. وقت 17 February 2019 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 2016-05-13. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 23. Springer Netherlands. 2006. pp. 75–102. doi:. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ↑ "Chloroplast DNA content in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae) from different cell cycle stages is consistent with kleptoplasty". Environ. Microbiol. 10 (9): 2411–7. September 2008. doi:. PMID 18518896. Bibcode: 2008EnvMi..10.2411M.

- ↑ "Did some red alga-derived plastids evolve via kleptoplastidy? A hypothesis". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 93 (1): 201–222. February 2018. doi:. PMID 28544184.

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002-01-01). "Molecular Motors". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26888/. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ↑ "Motor Proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 10 (5): a021931. May 2018. doi:. PMID 29716949.

- ↑ "Prokaryotic motility structures". Microbiology 149 (Pt 2): 295–304. February 2003. doi:. PMID 12624192.

- ↑ "Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Plant Physiology 127 (4): 1500–7. December 2001. doi:. PMID 11743094.

- ↑ The centrosome and its role in the organization of microtubules. International Review of Cytology. 106. 1987. pp. 227–293. doi:. ISBN 978-0-12-364506-7.

- ↑ The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2000. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-19-511183-5.

- ↑ "The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan". Journal of Experimental Botany 40 (1): 1–11. 1989. doi:.

- ↑ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0. https://archive.org/details/populationgeneti00hami.

- ↑ Taylor, TN; Kerp, H; Hass, H (2005). "Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (16): 5892–5897. doi:. PMID 15809414.

- ↑ "Energetics and genetics across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide". Biology Direct 6 (1): 35. June 2011. doi:. PMID 21714941.

- ↑ "The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sex". Journal of Molecular Evolution 48 (6): 779–783. June 1999. doi:. PMID 10229582. Bibcode: 1999JMolE..48..779D.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis". Current Biology 15 (2): 185–191. January 2005. doi:. PMID 15668177. Bibcode: 2005CBio...15..185R.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS ONE 3 (8): e2879. August 2007. doi:. PMID 18663385. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.2879M.

- ↑ "Demonstration of genetic exchange during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector". Science 324 (5924): 265–268. April 2009. doi:. PMID 19359589. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..265A.

- ↑ "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 278 (1715): 2081–2090. July 2011. doi:. PMID 21429931.

- ↑ سانچو:Cite Q

- ↑ "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina 23 (6): 361–373. 1980. doi:.

- ↑ Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber die Classification der Zoophyten" (de ۾). Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken 2 (6): 1008–1019. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/47614#page/530/mode/1up. Retrieved 15 March 2019. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (First class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are two columns per page.]

- ↑ "Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista". International Microbiology 2 (4): 207–221. 1999. PMID 10943416. http://www.im.microbios.org/08december99/03%20Scamardella.pdf.

- ↑ "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology 22 (2): 277–305. 1989. doi:. PMID 11542176. https://zenodo.org/record/1232387. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science 163 (3863): 150–60. January 1969. doi:. PMID 5762760. Bibcode: 1969Sci...163..150W.

- ↑ "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology 22 (2): 277–305. 1989. doi:. PMID 11542176. https://zenodo.org/record/1232387. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (12): 4576–4579. June 1990. doi:. PMID 2112744. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4576W.

- ↑ Knoll, Andrew H. (1992). "The Early Evolution of Eukaryotes: A Geological Perspective". Science 256 (5057): 622–627. doi:. PMID 1585174. Bibcode: 1992Sci...256..622K. "Eucarya, or eukaryotes".

- ↑ Margulis, Lynn (6 February 1996). "Archaeal-eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: phylogenetic classification of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93 (3): 1071–1076. doi:. PMID 8577716. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.1071M.

- ↑ "Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 283 (1823): 20152802. January 2016. doi:. PMID 26817772.

- ↑ "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66 (1): 4–119. January 2019. doi:. PMID 30257078.

- ↑ Brown, Matthew W.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Kamikawa, Ryoma; Inagaki, Yuji; Yabuki, Akinori; Tice, Alexander K; Shiratori, Takashi; Ishida, Ken-Ichiro et al. (2018-01-19). "Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group". Genome Biology and Evolution 10 (2): 427–433. doi:. PMID 29360967.

- ↑ "Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid". Nature Communications 12 (1): 6651. 2021. doi:. PMID 34789758. PMC 8599508. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-189959. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ↑ "Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes". Nature 612 (7941): 714–719. December 2022. doi:. PMID 36477531. Bibcode: 2022Natur.612..714T.

- ↑ "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2011. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=m3oFebknu1cC&pg=PA326. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology 75 (1): 631–647. October 2021. doi:. PMID 34343017.

- ↑ "Concepts of the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (3): 338–344. March 2019. doi:. PMID 30778187. Bibcode: 2019NatEE...3..338O.

- ↑ "Predatory protists". Current Biology 30 (10): R510–R516. May 2020. doi:. PMID 32428491. Bibcode: 2020CBio...30.R510L.

- ↑ "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature Communications 12 (1): 1879. March 2021. doi:. PMID 33767194. Bibcode: 2021NatCo..12.1879S.

- ↑ Koumandou, V. Lila; Wickstead, Bill; Ginger, Michael L.; van der Giezen, Mark; Dacks, Joel B.; Field, Mark C. (2013). "Molecular paleontology and complexity in the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 48 (4): 373–396. doi:. PMID 23895660.

- ↑ "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2011. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=m3oFebknu1cC&pg=PA326. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaean". Nature 613 (7943): 332–339. 2023. doi:. PMID 36544020. Bibcode: 2023Natur.613..332R.

- ↑ Miao, L.; Yin, Z.; Knoll, A. H.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, M. (2024). "1.63-billion-year-old multicellular eukaryotes from the Chuanlinggou Formation in North China". Science Advances 10 (4): eadk3208. doi:. PMID 38266082. Bibcode: 2024SciA...10K3208M.

- ↑ "Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old negaunee iron-formation, Michigan". Science 257 (5067): 232–5. July 1992. doi:. PMID 1631544. Bibcode: 1992Sci...257..232H.

- ↑ "Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 361 (1470): 1023–1038. June 2006. doi:. PMID 16754612.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa.". Precambrian Research 235: 71–87. 2013. doi:. Bibcode: 2013PreR..235...71R.

- ↑ "Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa.". Precambrian Research 235: 71–87. 2013. doi:. Bibcode: 2013PreR..235...71R.

- ↑ "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature 466 (7302): 100–104. July 2010. doi:. PMID 20596019. Bibcode: 2010Natur.466..100A.

- ↑ El Albani, Abderrazak (2023). "A search for life in Palaeoproterozoic marine sediments using Zn isotopes and geochemistry". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 623: 118169. doi:. Bibcode: 2023E&PSL.61218169E. https://hal.science/hal-04095643/file/El%20Albani%20et%20al._EPSL_2023.pdf.

- ↑ Ossa Ossa, Frantz; Pons, Marie-Laure; Bekker, Andrey; Hofmann, Axel; Poulton, Simon W.; Andersen, Morten B.; Agangi, Andrea; Gregory, Daniel et al. (2023). "Zinc enrichment and isotopic fractionation in a marine habitat of the c. 2.1 Ga Francevillian Group: A signature of zinc utilization by eukaryotes?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 611: 118147. doi:. Bibcode: 2023E&PSL.61118147O. https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/197720/8/1-s2.0-S0012821X23001607-main.pdf.

- ↑ Fakhraee, Mojtaba; Tarhan, Lidya G.; Reinhard, Christopher T.; Crowe, Sean A.; Lyons, Timothy W.; Planavsky, Noah J. (May 2023). "Earth's surface oxygenation and the rise of eukaryotic life: Relationships to the Lomagundi positive carbon isotope excursion revisited" (en ۾). Earth-Science Reviews 240: 104398. doi:. Bibcode: 2023ESRv..24004398F.

- ↑ "The controversial "Cambrian" fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (19): 7729–7734. May 2009. doi:. PMID 19416859. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.7729B.

- ↑ "Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes". Science 285 (5430): 1033–1036. August 1999. doi:. PMID 10446042. Bibcode: 1999Sci...285.1033B.

- ↑ Ward P. "Mass extinctions: the microbes strike back". New Scientist. صفحا. 40–43. وقت 8 July 2008 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 27 August 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (19): 5915–5920. May 2015. doi:. PMID 25918387. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.5915F.

- ↑ "Paleoproterozoic sterol biosynthesis and the rise of oxygen". Nature 543 (7645): 420–423. March 2017. doi:. PMID 28264195. Bibcode: 2017Natur.543..420G. https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20170407-083556533.

- ↑ "Sterol Synthesis in Diverse Bacteria". Frontiers in Microbiology 7: 990. 2016-06-24. doi:. PMID 27446030.

- ↑ "Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (25): e2101276118. June 2021. doi:. PMID 34131078. Bibcode: 2021PNAS..11801276H.

- ↑ "Tracking the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance with zinc isotopes". Geobiology 16 (4): 341–352. June 2018. doi:. PMID 29869832. Bibcode: 2018Gbio...16..341I.

- حوالن ۾ چُڪَ وارا صفحا

- غيرمددي پيراميٽر سان حوالا تي مشتمل صفحا

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Taxoboxes with no color

- سانچا

- LCCN سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- GND سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- BNF سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- Eukaryotes

- Articles containing video clips

- Domains (biology)

- Biology terminology

- حياتيات

- حيوانيات