مماليا

| Mammals | |

|---|---|

|

ٿن وارا جانور يا مئمل (mammals)، [1] مماليا جماعت جو هڪ فقاري جانور آهي. هن جانورن ۾ ٿن؛ کير پيدا ڪندڙ مئمري گلينڊ، جي موجودگيءَ، سندن ٻارن کي کير پيارڻ لاءِ، دماغ جو هڪ وسيع نيوڪورٽيڪس (neocortex) علائقو، فر يا وار ۽ ٽن وچين ڪنن جي هڏا، انهن کي ريپٽائلس ۽ پکين کان ڌار ڪن ٿا، جنهن مان سندن ابن ڏاڏن، ڪاربونيفئرس دور، 30 ڪروڙ سال اڳ، ۾ ڌار ٿي ويا هئا. تقريبن 6,400 موجود مماليا جي نوعن کي بيان ڪيو ويو آهي ۽ 29 آرڊرن ۾ ورهايو ويو آهي.

مئمل جو سڀ کان وڏو آرڊر، نوع جي تعداد جي لحاظ کان، ڪوئا، چمگادڙ ۽ يوليپوٽيفلا شامل آهن. ايندڙ ٽي ۾، پرائيميٽ (بشمول انسان، بندر ۽ ليمر)، اڍ ٿيل پير وارا انگوليٽ (جنهن ۾ سوئر، اُٺ ۽ وهيل شامل آهن) ۽ ڪارنيووروا (بشمول ٻليون، ڪتا ۽ سيل مڇي) شامل آهن.

مئمل سائناپسيڊا (Synapsida) جا واحد بچيل جانور آهن؛ هي ڪليڊ، ساروپسيڊا (Sauropsida) (ريڙهيون پائيندڙ ۽ پکين) سان گڏ ٿي، وڏو امنيوٽا (Amniota) ڪليڊ ٺاهي ٿو. ابتدائي سائناپسڊ (synapsids) کي "پيليڪوسارس" سڏيو ويندو آهي. وڌيڪ ترقي يافته، ٿيراپسڊ، گادالوپين دور جي دوران غالب ٿي ويا. مئمل سائنوڊونٽ (cynodonts)، ٿيراپسڊ جو هڪ ترقي يافته گروهه اهي، جيڪو آخري ٽراسيسڪ کان ابتدائي جوراسڪ دور ۾ پيدا ٿيو. مئمل پنهنجو جديد تنوع سينوزوئڪ دور جي پيليوجين ۽ نيوجين دورن ۾، غير ايوين ڊائنوسار جي ختم ٿيڻ کان پوءِ حاصل ڪيو ۽ 66 ملين سال اڳ کان وٺي اڄ تائين غالب زميني جانورن جو گروهه رهيو آهي.

مئمل جي بنيادي جسم جو قسم چوپايو (quadrupedal) آهي، اڪثر مئمل زميني حرڪت لاءِ چار پيرون (Limbs) استعمال ڪندا آهن؛ پر ڪن ۾، هي پير، سمنڊ ۾، هوا ۾، وڻن ۾ يا زير زمين زندگيءَ لاءِ ٺاهيا ويا آهن. بائپئڊ صرف ٻن هيٺين پيرن کي حرڪت ڪرڻ لاء موافقت ڪيو آهي، جڏهن ته سيٽيشين ۽ سامونڊي ڍڳي جا پوئين پير رڳو اندريون نشان آهن. مئمل جو ماپ 30 کان 40 مليميٽر (1.2-1.6 انچ)، ننڍي چمگادڙ کان، 30 ميٽر (98 فوٽ)، نيري وهيل، سڀ کان وڏو جانور جيڪا موجود آهن، تائين هوندو آهي. ڄمار ٻن سالن کان وهيل مڇي لاءِ 211 سالن تائين مختلف ٿئي ٿو. سڀ جديد مئمل ٻار کي جنم ڏين ٿا سواءِ مونوٽريمس جي پنجن قسمن جي، جيڪي آنا ڏين ٿا. سڀ کان وڌيڪ نسلن سان مالا مال گروپ ويويپارس پلئسنٽل مئمل آهي. انهن جو نالو عارضي عضوو (پلاسينٽا) لاءِ رکيو ويو آهي جيڪو اولاد پاران حمل دوران ماءُ کان غذائي حاصل ڪرڻ لاءِ استعمال ڪيو ويندو آهي.

اڪثر مئمل ذهانت وارا هوندا آهن، جن ۾ ڪي وڏا دماغ، خود آگاهي ۽ اوزار جي استعمال سان واقفيت وارا هوندا آهن. مئمل ڪيترن ئي طريقن سان ڳالهه ٻولهه ۽ آواز ڏئي سگھن ٿا، جن ۾ الٽراسائونڊ جي پيداوار، خوشبوءِ نشان لڳائڻ، الارم سگنلز، ڳائڻ، ايڪولوڪيشن؛ ۽ انسانن جي صورت ۾، پيچيده ٻولين جا مالڪ آهن. مئمل پاڻ کي ٽٽڻ-جوڙڻ واري خاندان ۽ درجه بندي ۾ منظم ڪري سگهن ٿا، پر اڪيلائي ۽ علائقائي به ٿي سگهن ٿا. گهڻا مئمل پولي گائنس هوندا آهن، پر ڪجهه مونو گائنس يا پولي ائنڊرس ٿي سگهن ٿا.

انسانن پاران ڪيترن ئي قسمن جي مئمل جانور کي پالڻ نيو پاولٿڪ انقلاب ۾ اهم ڪردار ادا ڪيو ۽ ان جي نتيجي ۾ شڪار ۽ گڏ ڪرڻ جي جاءِ تي زراعت کي انسانن لاءِ خوراڪ جو بنيادي ذريعو بڻايو ويو، ج انساني سماجن جي هڪ وڏي بحاليءَ جو سبب بڻجي ويو، جنهن ۾ خانه بدوشي کان وڏين گروهن جي وچ ۾ وڌيڪ تعاون سان مستقل رهائش تائين ۽ آخرڪار پهرين تهذيبن جي ترقي ٿي. پالتو جانور ٽرانسپورٽ ۽ زراعت لاء طاقت، گڏوگڏ خوراڪ (گوشت ۽ کير جون شيون)، فر ۽ چمڙي مهيا ڪيا ۽ مهيا ڪرڻ جاري رکو آهي.

مئمل پڻ شڪار ڪيا ويندا آهن ۽ راندين لاءِ ڊوڙايا ويندا آهن، انهن کي پالتو جانور ۽ مختلف قسمن جا ڪم ڪندڙ جانورن طور رکيو ويندو آهي ۽ سائنس ۾ ماڊل آرگنزم طور استعمال ٿيندا آهن. مئمل کي پيليولٿڪ زماني کان وٺي فن ۾ ڏيکاريو ويو آهي ۽ ادب، فلم ۽ مذهب ۾ ظاهر ڪيو ويو آهي. انهن جي انگن ۾ گهٽتائي ۽ ڪيترن ئي ٿڻ واري جانورن جي ختم ٿيڻ جو سبب بنيادي طور تي انساني شڪار ۽ رهائش جي تباهي، بنيادي طور تي جنگلات جي تباهي آهي.

درجه بندي

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو مماليا جي درجابندي

جڏهن کان ڪارل لينيئي شروعاتي طور تي طبقن جي وضاحت ڪئي هئي ۽ هن وقت جڏهن، ڪابه درجه بندي نظام کي عالمي طور تي قبول نه ڪيو ويو آهي، مماليا جي درجي بندي ڪيترن ئي ترميمن جي ذريعي ڪئي وئي آهي. ميڪينا ۽ بئل (1997) ۽ ولسن ۽ ريڊر (2005) مفيد مجموعا مهيا ڪن ٿا.[2] سمپسن (1945) مماليا جي اصليت ۽ رشتن جي نظميات مهيا ڪري ٿو جيڪا 20هين صدي جي آخر تائين عالمي طور تي سيکاريا ويا هئا.[3] بهرحال، سال 1945ع کان وٺي، نئين ۽ وڌيڪ تفصيلي ڄاڻ جو هڪ وڏو مقدار آهستي آهستي مليو آهي؛ پيلئنٽالاجي رڪارڊ کي ٻيهر ترتيب ڏنو ويو آهي ۽ وچئين سالن ۾، جزوي طور تي ڪليڊسٽڪس جي نئين تصور ذريعي، خود نظام سازي جي نظرياتي بنيادن جي باري ۾ تمام گهڻو بحث ۽ پيش رفت ڏٺو آهي. جيتوڻيڪ فيلڊ ورڪ ۽ ليبارٽري ڪم ترقي يافته طور تي سمپسن جي درجه بندي کي ختم ڪري ڇڏيو آهي، اهو معلوم مسئلن جي باوجود، مماليا جي آفيشيل درجه بندي جي ويجهو آهي.[4]

سڀ کان وڌيڪ مماليا، جن ۾ ڇھ سڀ کان وڌيڪ نوعن سان مالا مال آرڊر شامل آھن، پلئسينٽل گروپ سان تعلق رکن ٿا. نسلن جي تعداد ۾ ٽي سڀ کان وڏا آرڊر آهن؛

- روڊينشيا: ڪوئا، پورڪيوپينز، بيور، ڪيپيبارا ۽ ٻيا ٿڌڙا جانور

- ڪروپٽيرا: چمگادڙون ۽

- يوليپوٽائيڦلا: شريو، مولز ۽ سولينوڊون

ايندڙ ٽي وڏا آرڊر، جيڪا استعمال ٿيل حياتياتي درجه بندي منصوبي تي منحصر ڪرن ٿا، هيٽ آهن؛

- پرائيميٽ: بن مانس، بندر ۽ ليمر

- سئٽارٽيوڊڪٽائلا: وهيل مڇي، اٺ، سوئر وغيره ۽

- ڪارنيوورا: جنهن ۾ شينهن، ڪتا، ٻليون، ريڙ، سيل مڇي ۽ اتحادي شامل آهن.[5]

ميمل اسپيسيز آف دي ورلڊ جي مطابق، 2006ع ۾ 5,416 نوعن جي سڃاڻپ ڪئي وئي. انھن کي 1,229 نسلن، 153 خاندانن ۽ 29 آرڊرن ۾ ورهايو ويو.[6] 2008ع ۾، انٽرنيشنل يونين فار ڪنزرويشن آف نيچر (IUCN) پنهنجي IUCN جي ريڊ لسٽ لاءِ پنجن سالن جي عالمي درجابندي جو جائزو مڪمل ڪيو، جنهن ۾ 5,488 نسلن جي ڳڻپ ڪئي وئي.[7] سال 2018ع ۾ جرنل آف ميمالاجي ۾ شايع ٿيل تحقيق مطابق، تسليم ٿيل مماليا جي نسلن جو تعداد 6,495 آهي، جن ۾ 96 تازو ئي معدوم/ختم ٿي ويا آهن.[8]

تعريف

[سنواريو]لفظ "مئمل" جديد آهي، جيڪو سائنسي نالي "مئمليا" (Mammalia) مان نڪتل آهي، جيڪو 1758ع ۾ ڪارل لنيئي ٺاهيو هو، جيڪو لاطيني لفظ، "مما" (Mamma يعني پستان) مان نڪتل آهي. 1988ع جي هڪ با اثر جرنل ۾، ٽموٿي روئي "مئمليا" جي ڦائلوجئنيٽيڪل طور تي وضاحت ڪئي ته مماليا جو تاج گروپ، ڪليڊ جنهن ۾ سڀ کان تازو عام جاندار مونوٽريمس (ڪڊناس ۽ پلئٽيپس) ۽ ٿيريئن مماليا (مارسوپيئلز ۽ پلئسينٽل) ۽ ان جي سڀني نسلن تي مشتمل آهي. جيئن ته هن جا ابا ڏاڏا جراسڪ دور ۾ رهندا هئا، روئي جي تعريف سڀني جانورن کي اڳئين ٽراسڪ دور مان خارج ڪري ٿي، ان حقيقت جي باوجود ته هارميڊيا ۾ ٽراسڪ فوسلز 19هين صدي جي وچ کان وٺي مماليا جي حوالي ڪيا ويا آهن. جيڪڏهن مئمليا کي تاج گروهه سمجهيو وڃي، ته ان جي اصليت جو اندازو لڳائي سگهجي ٿو جيئن جانورن جي پهرين ڄاتل ظاهري طور تي ٻين جي ڀيٽ ۾ ڪجهه موجود مماليا سان وڌيڪ ويجهي سان لاڳاپيل آهي. ٽي.ايس. ڪيمپ هڪ وڌيڪ روايتي تعريف مهيا ڪئي آهي ته "سائناپسڊ جن ۾، مٿين ۽ هيٺين دانت جي وچ ۾، حرڪت لاء هڪ ٽرانسورس جزو سان، يا برابر طور تي، ڏندن جي علامت آهي"، ڪيمپ جي نظر ۾، سينوڪونڊون ۽ جيئري مماليا جي آخري عام ابن ڏاڏن سان پيدا ٿيندڙ ڪليڊ آهي. سڀ کان پهرين مشهور سائناپسڊ، ڪيمپ جي تعريف کي مطمئن ڪندڙ، ٽڪيٿيريئم (Tikitherium) آهي، تنهنڪري مماليا جي ظاهر ٿيڻ هن وسيع معنى ۾ هن آخري ٽرائيئسڪ تاريخ ڏئي سگهجي ٿو.

The word "mammal" is modern, from the scientific name Mammalia coined by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, derived from the Latin mamma ("teat, pap"). In an influential 1988 paper, Timothy Rowe defined Mammalia phylogenetically as the crown group of mammals, the clade consisting of the most recent common ancestor of living monotremes (echidnas and platypuses) and therian mammals (marsupials and placentals) and all descendants of that ancestor.[9] Since this ancestor lived in the Jurassic period, Rowe's definition excludes all animals from the earlier Triassic, despite the fact that Triassic fossils in the Haramiyida have been referred to the Mammalia since the mid-19th century.[10] If Mammalia is considered as the crown group, its origin can be roughly dated as the first known appearance of animals more closely related to some extant mammals than to others. Ambondro is more closely related to monotremes than to therian mammals while Amphilestes and Amphitherium are more closely related to the therians; as fossils of all three genera are dated about سانچو:Ma in the Middle Jurassic, this is a reasonable estimate for the appearance of the crown group.[11]

T. S. Kemp has provided a more traditional definition: "Synapsids that possess a dentary–squamosal jaw articulation and occlusion between upper and lower molars with a transverse component to the movement" or, equivalently in Kemp's view, the clade originating with the last common ancestor of Sinoconodon and living mammals.[12] The earliest-known synapsid satisfying Kemp's definitions is Tikitherium, dated سانچو:Ma, so the appearance of mammals in this broader sense can be given this Late Triassic date.[13][14] However, this animal may have actually evolved during the Neogene.[15]

Molecular classification of placentals

[سنواريو]

As of the early 21st century, molecular studies based on DNA analysis have suggested new relationships among mammal families. Most of these findings have been independently validated by retrotransposon presence/absence data.[17] Classification systems based on molecular studies reveal three major groups or lineages of placental mammals—Afrotheria, Xenarthra and Boreoeutheria—which diverged in the Cretaceous. The relationships between these three lineages is contentious, and all three possible hypotheses have been proposed with respect to which group is basal. These hypotheses are Atlantogenata (basal Boreoeutheria), Epitheria (basal Xenarthra) and Exafroplacentalia (basal Afrotheria).[18] Boreoeutheria in turn contains two major lineages—Euarchontoglires and Laurasiatheria.

Estimates for the divergence times between these three placental groups range from 105 to 120 million years ago, depending on the type of DNA used (such as nuclear or mitochondrial)[19] and varying interpretations of paleogeographic data.[18]

| Tarver et al. 2016[20] | Sandra Álvarez-Carretero et al. 2022[21][22] |

|---|---|

ارتقا

[سنواريو]اناتومي

[سنواريو]رويا

[سنواريو]انسان ۽ ٻيا مئمل

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Human uses of mammals

انساني تهذيب ۾

[سنواريو]

Non-human mammals play a wide variety of roles in human culture. They are the most popular of pets, with tens of millions of dogs, cats and other animals including rabbits and mice kept by families around the world.[23][24][25] Mammals such as mammoths, horses and deer are among the earliest subjects of art, being found in Upper Paleolithic cave paintings such as at Lascaux.[26] Major artists such as Albrecht Dürer, George Stubbs and Edwin Landseer are known for their portraits of mammals.[27] Many species of mammals have been hunted for sport and for food; deer and wild boar are especially popular as game animals.[28][29][30] Mammals such as horses and dogs are widely raced for sport, often combined with betting on the outcome.[31][32] There is a tension between the role of animals as companions to humans, and their existence as individuals with rights of their own.[33] Mammals further play a wide variety of roles in literature,[34][35][36] film,[37] mythology, and religion.[38][39][40]

استعمال ۽ اهميت

[سنواريو]

The domestication of mammals was instrumental in the Neolithic development of agriculture and of civilization, causing farmers to replace hunter-gatherers around the world.[lower-alpha 1][42] This transition from hunting and gathering to herding flocks and growing crops was a major step in human history. The new agricultural economies, based on domesticated mammals, caused "radical restructuring of human societies, worldwide alterations in biodiversity, and significant changes in the Earth's landforms and its atmosphere... momentous outcomes".[43]

Domestic mammals form a large part of the livestock raised for meat across the world. They include (2009) around 1.4 billion cattle, 1 billion sheep, 1 billion domestic pigs,[44][45] and (1985) over 700 million rabbits.[46] Working domestic animals including cattle and horses have been used for work and transport from the origins of agriculture, their numbers declining with the arrival of mechanised transport and agricultural machinery. In 2004 they still provided some 80% of the power for the mainly small farms in the third world, and some 20% of the world's transport, again mainly in rural areas. In mountainous regions unsuitable for wheeled vehicles, pack animals continue to transport goods.[47] Mammal skins provide leather for shoes, clothing and upholstery. Wool from mammals including sheep, goats and alpacas has been used for centuries for clothing.[48][49]

Mammals serve a major role in science as experimental animals, both in fundamental biological research, such as in genetics,[51] and in the development of new medicines, which must be tested exhaustively to demonstrate their safety.[52] Millions of mammals, especially mice and rats, are used in experiments each year.[53] A knockout mouse is a genetically modified mouse with an inactivated gene, replaced or disrupted with an artificial piece of DNA. They enable the study of sequenced genes whose functions are unknown.[54] A small percentage of the mammals are non-human primates, used in research for their similarity to humans.[55][56][57]

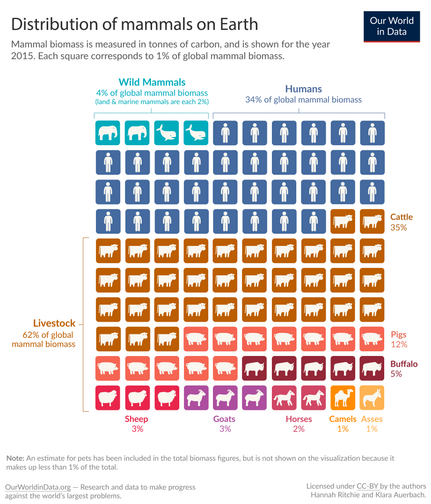

Despite the benefits domesticated mammals had for human development, humans have an increasingly detrimental effect on wild mammals across the world. It has been estimated that the mass of all wild mammals has declined to only 4% of all mammals, with 96% of mammals being humans and their livestock now (see figure). In fact, terrestrial wild mammals make up only 2% of all mammals.[58][59]

مخلوط نسلون

[سنواريو]- اصل مضمون جي لاءِ ڏسو Hybrid (biology)

Hybrids are offspring resulting from the breeding of two genetically distinct individuals, which usually will result in a high degree of heterozygosity, though hybrid and heterozygous are not synonymous. The deliberate or accidental hybridizing of two or more species of closely related animals through captive breeding is a human activity which has been in existence for millennia and has grown for economic purposes.[60] Hybrids between different subspecies within a species (such as between the Bengal tiger and Siberian tiger) are known as intra-specific hybrids. Hybrids between different species within the same genus (such as between lions and tigers) are known as interspecific hybrids or crosses. Hybrids between different genera (such as between sheep and goats) are known as intergeneric hybrids.[61] Natural hybrids will occur in hybrid zones, where two populations of species within the same genera or species living in the same or adjacent areas will interbreed with each other. Some hybrids have been recognized as species, such as the red wolf (though this is controversial).[62]

Artificial selection, the deliberate selective breeding of domestic animals, is being used to breed back recently extinct animals in an attempt to achieve an animal breed with a phenotype that resembles that extinct wildtype ancestor. A breeding-back (intraspecific) hybrid may be very similar to the extinct wildtype in appearance, ecological niche and to some extent genetics, but the initial gene pool of that wild type is lost forever with its extinction. As a result, bred-back breeds are at best vague look-alikes of extinct wildtypes, as Heck cattle are of the aurochs.[63]

Purebred wild species evolved to a specific ecology can be threatened with extinction[64] through the process of genetic pollution, the uncontrolled hybridization, introgression genetic swamping which leads to homogenization or out-competition from the heterosic hybrid species.[65] When new populations are imported or selectively bred by people, or when habitat modification brings previously isolated species into contact, extinction in some species, especially rare varieties, is possible.[66] Interbreeding can swamp the rarer gene pool and create hybrids, depleting the purebred gene pool. For example, the endangered wild water buffalo is most threatened with extinction by genetic pollution from the domestic water buffalo. Such extinctions are not always apparent from a morphological standpoint. Some degree of gene flow is a normal evolutionary process, nevertheless, hybridization threatens the existence of rare species.[67][68]

خطرا

[سنواريو]

The loss of species from ecological communities, defaunation, is primarily driven by human activity.[69] This has resulted in empty forests, ecological communities depleted of large vertebrates.[70][71] In the Quaternary extinction event, the mass die-off of megafaunal variety coincided with the appearance of humans, suggesting a human influence. One hypothesis is that humans hunted large mammals, such as the woolly mammoth, into extinction.[72][73] The 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by IPBES states that the total biomass of wild mammals has declined by 82 percent since the beginning of human civilization.[74][75] Wild animals make up just 4% of mammalian biomass on earth, while humans and their domesticated animals make up 96%.[59]

Various species are predicted to become extinct in the near future,[76] among them the rhinoceros,[77] giraffes,[78] and species of primates[79] and pangolins.[80] According to the WWF's 2020 Living Planet Report, vertebrate wildlife populations have declined by 68% since 1970 as a result of human activities, particularly overconsumption, population growth and intensive farming, which is evidence that humans have triggered a sixth mass extinction event.[81][82] Hunting alone threatens hundreds of mammalian species around the world.[83][84] Scientists claim that the growing demand for meat is contributing to biodiversity loss as this is a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction; species-rich habitats, such as significant portions of the Amazon rainforest, are being converted to agricultural land for meat production.[85][86][87] Another influence is over-hunting and poaching, which can reduce the overall population of game animals,[88] especially those located near villages,[89] as in the case of peccaries.[90] The effects of poaching can especially be seen in the ivory trade with African elephants.[91] Marine mammals are at risk from entanglement from fishing gear, notably cetaceans, with discard mortalities ranging from 65,000 to 86,000 individuals annually.[92]

Attention is being given to endangered species globally, notably through the Convention on Biological Diversity, otherwise known as the Rio Accord, which includes 189 signatory countries that are focused on identifying endangered species and habitats.[93] Another notable conservation organization is the IUCN, which has a membership of over 1,200 governmental and non-governmental organizations.[94]

Recent extinctions can be directly attributed to human influences.[95][69] The IUCN characterizes 'recent' extinction as those that have occurred past the cut-off point of 1500,[96] and around 80 mammal species have gone extinct since that time and 2015.[97] Some species, such as the Père David's deer[98] are extinct in the wild, and survive solely in captive populations. Other species, such as the Florida panther, are ecologically extinct, surviving in such low numbers that they essentially have no impact on the ecosystem.[99]:318 Other populations are only locally extinct (extirpated), still existing elsewhere, but reduced in distribution,[99]:75–77 as with the extinction of gray whales in the Atlantic.[100]

پڻ ڏسو

[سنواريو]- مماليا جي نسلن جي فهرست - موجود مماليا

- مئمالوجسٽ جي فهرست

- مونوٽريمز ۽ مارسوپيئلز جي فهرست

- پلئسينٽل مماليا جي فهرست

- قبل از تاريخ مماليا جي فهرست

- خطري جي زد ۾ مماليا جي فهرست

- آبادي جي ماپ جي لحاظ کان مماليا جي فهرست

- علائقي جي لحاظ کان مماليا جي فهرست

- 2000s ۾ بيان ڪيل مماليا جي فهرست

- مماليا ثقافت ۾

- ننڍا مماليا

ٿن وارا جانور يا مئمل (mammals) يا کير ڌارائيندڙ جانور اها جانور آهن، جنهن جا ٿڻ هوندا آهن ۽ جيڪي پنهنجي ٻچن کي کير پياريندا آهن. ھي جانور ڪرنگهي واري جانورن جي هڪ جماعت آهن.

خارجي لنڪس

[سنواريو]| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of |

- ASM Mammal Diversity Database آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 25 December 2022 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين.

- Biodiversitymapping.org – All mammal orders in the world with distribution maps آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 2016-09-26 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين.

- Paleocene Mammals آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 3 February 2024 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين., a site covering the rise of the mammals, paleocene-mammals.de

- Evolution of Mammals آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 25 January 2024 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين., a brief introduction to early mammals, enchantedlearning.com

- European Mammal Atlas EMMA آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 25 January 2024 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين. from Societas Europaea Mammalogica, European-mammals.org

- Marine Mammals of the World آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 8 June 2019 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين. – An overview of all marine mammals, including descriptions, both fully aquatic and semi-aquatic, noaa.gov

- Mammalogy.org آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 1 March 2020 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين. The American Society of Mammalogists was established in 1919 for the purpose of promoting the study of mammals, and this website includes a mammal image library

سانچو:Chordata سانچو:Cynodontia سانچو:Basal mammals سانچو:Mammals

حوالا

[سنواريو]- ↑ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles. "mamma". A Latin Dictionary. Perseus Digital Library. وقت 29 September 2022 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 29 September 2022. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Classification of Mammals". Mammalogy (6th ed.). Jones and Bartlett Learning. 2013. ISBN 978-1-284-03209-3.

- ↑ "Principles of classification, and a classification of mammals". American Museum of Natural History 85. 1945.

- ↑ "Classification of mammals above the species level: Review". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19 (1): 191–195. 1999. doi:. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ سانچو:MSW3

- ↑ سانچو:MSW3

- ↑ "Mammals". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). وقت 3 September 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 23 August 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "How many species of mammals are there?". Journal of Mammalogy 99 (1): 1–14. 1 February 2018. doi:.

- ↑ "Definition, diagnosis, and origin of Mammalia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 8 (3): 241–264. 1988. doi:. Bibcode: 1988JVPal...8..241R. https://www.geo.utexas.edu/faculty/rowe/Publications/pdf/010%20Rowe%201988.pdf. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ↑ The Student's Elements of Geology. London: John Murray. 1871. p. 347. ISBN 978-1-345-18248-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=634gAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA347.

- ↑ "Paleontology. Marsupial origins". Science 302 (5652): 1899–1900. December 2003. doi:. PMID 14671280.

- ↑ The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-850760-4. OCLC 232311794. https://doc.rero.ch/record/200125/files/PAL_E3904.pdf. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ↑ "Earliest mammal with transversely expanded upper molar from the Late Triassic (Carnian) Tiki Formation, South Rewa Gondwana Basin, India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (1): 200–207. 2005. doi:.

- ↑ "Analysis of Molar Structure and Phylogeny of Docodont Genera". Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 39: 27–47. 2007. doi:. https://xa.yimg.com/kq/groups/13543816/1018125207/name/Luo+y+Martin+2007-+molar+structure+and+phylogeny+of+docodonts.pdf. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Averianov, Alexander O.; Voyta, Leonid L. (March 2024). "Putative Triassic stem mammal Tikitherium copei is a Neogene shrew" (en ۾). Journal of Mammalian Evolution 31 (1). doi:. ISSN 1064-7554. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10914-024-09703-w.

- ↑ "Retroposed elements as archives for the evolutionary history of placental mammals". PLOS Biology 4 (4): e91. April 2006. doi:. PMID 16515367.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Retroposon analysis and recent geological data suggest near-simultaneous divergence of the three superorders of mammals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (13): 5235–5240. March 2009. doi:. PMID 19286970. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.5235N.

- ↑ "Placental mammal diversification and the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (3): 1056–1061. February 2003. doi:. PMID 12552136. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.1056S.

- ↑ "The Interrelationships of Placental Mammals and the Limits of Phylogenetic Inference". Genome Biology and Evolution 8 (2): 330–344. January 2016. doi:. PMID 26733575.

- ↑ "A species-level timeline of mammal evolution integrating phylogenomic data". Nature 602 (7896): 263–267. 2022. doi:. PMID 34937052. Bibcode: 2022Natur.602..263A. https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/75979.

- ↑ Alvarez-Carretero, Sandra; Tamuri, Asif; Battini, Matteo; Nascimento, Fabricia F.; Carlisle, Emily; Asher, Robert; Yang, Ziheng; Donoghue, Philip et al. (2021). Data for A Species-Level Timeline of Mammal Evolution Integrating Phylogenomic Data. doi:. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Data_for_A_Species-Level_Timeline_of_Mammal_Evolution_Integrating_Phylogenomic_Data_/14885691. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ "Animals in healthcare facilities: recommendations to minimize potential risks". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 36 (5): 495–516. May 2015. doi:. PMID 25998315. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/7086725BAB2AAA4C1949DA5B90F06F3B/S0899823X1500015Xa.pdf/div-class-title-animals-in-healthcare-facilities-recommendations-to-minimize-potential-risks-div.pdf.

- ↑ The Humane Society of the United States. "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". وقت 7 April 2012 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 27 April 2012. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ USDA. "U.S. Rabbit Industry profile" (PDF). وقت 7 August 2019 تي اصل (PDF) کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 10 July 2013. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Prehistoric cave art in the Dordogne". The Guardian. 26 May 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2013/may/26/prehistoric-cave-art-dordogne.

- ↑ "The top 10 animal portraits in art". The Guardian. 27 June 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2014/jun/27/top-10-animal-portraits-in-art.

- ↑ "Deer Hunting in the United States: An Analysis of Hunter Demographics and Behavior Addendum to the 2001 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation Report 2001-6". Fishery and Wildlife Service (US). وقت 13 August 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 24 June 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Shelton L. "Recreational Hog Hunting Popularity Soaring". The Natchez Democrat. Grand View Outdoors. وقت 12 December 2017 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 24 June 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Hunting For Food: Guide to Harvesting, Field Dressing and Cooking Wild Game. F+W Media. 2015. pp. 6–77. ISBN 978-1-4403-3856-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=3XN6CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA6. Chapters on hunting deer, wild hog (boar), rabbit, and squirrel.

- ↑ "Horse racing". The Encyclopædia Britannica. وقت 21 December 2013 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Greyhound Racing. Pelham Books. 1981. ISBN 978-0-7207-1106-6. OCLC 9324926.

- ↑ "The Role of Animals in Human Society". Journal of Social Issues 49 (1): 1–9. 1993. doi:.

- ↑ "Top 10 books about intelligent animals". The Guardian. 26 March 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/26/top-10-books-intelligent-animals-watership-down-animal-farm.

- ↑ Exploring Children's Literature (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. 2008. ISBN 978-1-4129-3013-0. OCLC 71285210.

- ↑ "Books for Adults". Seal Sitters. وقت 11 July 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 9 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Animals in Film and Media". Oxford Bibliographies. 2013. doi:.

- ↑ Cattle: History, Myth, Art. London: The British Museum Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-7141-5084-0. OCLC 665137673.

- ↑ Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. p. 9.

- ↑ Grainger R. "Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions". ALERT. وقت 23 September 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Part 2: The rise and spread of food production". Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1997. ISBN 978-0-393-03891-0. OCLC 35792200. https://books.google.com/books?id=PWnWRFEGoeUC&pg=PA176.

- ↑ "A population genetics view of animal domestication". Trends in Genetics 29 (4): 197–205. April 2013. doi:. PMID 23415592. https://www.palaeobarn.com/sites/domestication.org.uk/files/downloads/98.pdf. Retrieved 9 November 2016. آرڪائيو ڪيا ويا 8 June 2019 حوالو موجود آهي وي بيڪ مشين.

- ↑ "Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (33): 11597–11604. August 2008. doi:. PMID 18697943. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10511597Z.

- ↑ "Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens". The Economist. 27 July 2011. https://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/07/global-livestock-counts.

- ↑ "Breeds of Cattle at CATTLE TODAY". Cattle Today. Cattle-today.com. وقت 15 July 2011 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Lukefahr SD, Cheeke PR. "Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems". Food and Agriculture Organization. وقت 6 May 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Encyclopedia of Animal Science. CRC Press. 2004. pp. 248–250. ISBN 978-0-8247-5496-9. OCLC 57033325. https://books.google.com/books?id=1SQl7Ao3mHoC&pg=PA248. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ "Wool". Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion. 3. Thomson Gale. 2005. pp. 441–443. ISBN 978-0-684-31394-8. OCLC 963977000. https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofcl00vale/page/441.

- ↑ "Alpaca: An Ancient Luxury". Interweave Knits: 74–76. Fall 2000.

- ↑ "Wild mammals make up only a few percent of the world's mammals". Our World in Data. حاصل ڪيل 2023-08-08.

- ↑ "Genetics Research". Animal Health Trust. وقت 12 December 2017 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Drug Development". Animal Research.info. وقت 8 June 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers". Speaking of Research. وقت 24 April 2019 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 6 November 2016. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "It's a knockout". Nature. 2003. doi:. https://www.nature.com/news/1998/030512/full/news030512-17.html. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ↑ "The supply and use of primates in the EU". European Biomedical Research Association. وقت 2012-01-17 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل.

- ↑ "Use of primates in research: a global overview". American Journal of Primatology 63 (4): 225–237. August 2004. doi:. PMID 15300710.

- ↑ Weatherall D, ۽ ٻيو. The use of non-human primates in research (PDF) (Report). London: Academy of Medical Sciences. وقت 2013-03-23 تي اصل (PDF) کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Biodiversity". Our World in Data. 2021-04-15. https://ourworldindata.org/mammals. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115 (25): 6506–6511. June 2018. doi:. PMID 29784790. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.6506B.

- ↑ Principles and applications of domestic animal behavior: an introductory text. Sacramento: Cambridge University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-1-84593-398-2. OCLC 226038028. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ww07sIWTYAAC&pg=PA228.

- ↑ Chimbrids – Chimeras and Hybrids in Comparative European and International Research. Heidelberg: Springer. 2009. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-540-93869-9. OCLC 495479133. https://books.google.com/books?id=O3M4qfxtGhIC&pg=PA13.

- ↑ "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Fauna 77: 2. 2012. doi:. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc700981/. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ↑ Retracing the Aurochs – History, Morphology and Ecology of an extinct wild Ox. Pensoft Publishers. 2005. ISBN 978-954-642-235-4. OCLC 940879282.

- ↑ "The evolutionary impact of invasive species". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (10): 5446–5451. May 2001. doi:. PMID 11344292. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...98.5446M.

- ↑ "Genetic analysis shows low levels of hybridization between African wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica) and domestic cats (F. s. catus) in South Africa". Ecology and Evolution 5 (2): 288–299. January 2015. doi:. PMID 25691958. Bibcode: 2015EcoEv...5..288L.

- ↑ Australia's state of the forests report. 2003. p. 107.

- ↑ "Extinction by Hybridization and Introgression". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 27: 83–109. November 1996. doi:.

- ↑ Genetic pollution from farm forestry using eucalypt species and hybrids: a report for the RIRDC/L&WA/FWPRDC Joint Venture Agroforestry Program. Rural Industrial Research and Development Corporation of Australia. 2001. ISBN 978-0-642-58336-9. OCLC 48794104.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 "Defaunation in the Anthropocene". Science 345 (6195): 401–406. July 2014. doi:. PMID 25061202. Bibcode: 2014Sci...345..401D. https://www.uv.mx/personal/tcarmona/files/2010/08/Science-2014-Dirzo-401-6-2.pdf. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ↑ Essentials of Conservation Biology (6th ed.). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers. 2014. pp. 217–245. ISBN 978-1-60535-289-3. OCLC 876140621.

- ↑ "Vanishing fauna. Introduction". Science 345 (6195): 392–395. July 2014. doi:. PMID 25061199. Bibcode: 2014Sci...345..392V.

- ↑ "Fifty millennia of catastrophic extinctions after human contact". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20 (7): 395–401. July 2005. doi:. PMID 16701402. https://www.anthropology.hawaii.edu/Fieldschools/Kauai/Publications/Publication%204.pdf.

- ↑ "Historic extinctions: a Rosetta stone for understanding prehistoric extinctions". Quaternary extinctions: A prehistoric revolution. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 1984. pp. 824–862. ISBN 978-0-8165-1100-6. OCLC 10301944.

- ↑ "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. 6 May 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/06/human-society-under-urgent-threat-loss-earth-natural-life-un-report.

- ↑ "Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. 6 May 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-48169783.

- ↑ Main D. "7 Iconic Animals Humans Are Driving to Extinction". Live Science. وقت 6 January 2023 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 25 January 2024. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ Platt JR. "Poachers Drive Javan Rhino to Extinction in Vietnam". Scientific American. وقت 6 April 2015 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل.

- ↑ "Giraffes facing extinction after devastating decline, experts warn". The Guardian. 8 December 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/dec/08/giraffe-red-list-vulnerable-species-extinction.

- ↑ "Impending extinction crisis of the world's primates: Why primates matter". Science Advances 3 (1): e1600946. January 2017. doi:. PMID 28116351. Bibcode: 2017SciA....3E0946E.

- ↑ "Pangolins: why this cute prehistoric mammal is facing extinction". The Telegraph. 31 January 2015. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/wildlife/11370277/Pangolins-why-this-cute-prehistoric-mammal-is-facing-extinction.html.

- ↑ "Humans exploiting and destroying nature on unprecedented scale – report". The Guardian. 9 September 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/10/humans-exploiting-and-destroying-nature-on-unprecedented-scale-report-aoe.

- ↑ "Terrifying wildlife losses show the extinction end game has begun – but it's not too late for change". The Independent. 1 October 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/wildlife-loss-humans-population-agriculture-extinction-b738367.html.

- ↑ Pennisi E. "People are hunting primates, bats, and other mammals to extinction". Science. وقت 20 October 2021 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 3 February 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Bushmeat hunting and extinction risk to the world's mammals". Royal Society Open Science 3 (10): 160498. October 2016. doi:. PMID 27853564. Bibcode: 2016RSOS....360498R.

- ↑ "The Anthropocene Biosphere". The Anthropocene Review 2 (3): 196–219. 2015. doi:. Bibcode: 2015AntRv...2..196W.

- ↑ Morell V. "Meat-eaters may speed worldwide species extinction, study warns". Science. وقت 20 December 2016 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 3 February 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". The Science of the Total Environment 536: 419–431. December 2015. doi:. PMID 26231772. Bibcode: 2015ScTEn.536..419M.

- ↑ "The empty forest". BioScience 42 (6): 412–422. 1992. doi:. http://www.dse.ufpb.br/alexandre/Redford%201992%20-The%20empty%20forest.pdf. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ↑ "Impact of game hunting by the Kayapó of south-eastern Amazonia: implications for wildlife conservation in tropical forest indigenous reserves". Human Exploitation and Biodiversity Conservation. 3. Springer. 2006. pp. 287–313. ISBN 978-1-4020-5283-5. OCLC 207259298.

- ↑ "Distribution and Relative Abundance of Peccaries in the Argentine Chaco: Associations with Human Factors". Biological Conservation 116 (2): 217–225. 2004. doi:. Bibcode: 2004BCons.116..217A.

- ↑ Gobush K. "Effects of Poaching on African elephants". Center For Conservation Biology. University of Washington. وقت 8 December 2021 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 12 May 2021. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Bycatch of Marine Mammals". A global assessment of fisheries bycatch and discards. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1996. ISBN 978-92-5-103555-9. OCLC 31424005. https://www.fao.org/docrep/003/t4890e/T4890E03.htm#ch1.1.10. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ↑ IUCN environmental policy and law paper. Guide to the Convention on Biodiversity. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 1994. ISBN 978-2-8317-0222-3. OCLC 32201845.

- ↑ "About IUCN". International Union for Conservation of Nature. وقت 15 April 2020 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 3 February 2017. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ "Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction". Science Advances 1 (5): e1400253. June 2015. doi:. PMID 26601195. Bibcode: 2015SciA....1E0253C.

- ↑ "Correlates of rediscovery and the detectability of extinction in mammals". Proceedings. Biological Sciences 278 (1708): 1090–1097. April 2011. doi:. PMID 20880890.

- ↑ The Annihilation of Nature: Human Extinction of Birds and Mammals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2015. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-4214-1718-9.

- ↑ Jiang, Z.; Harris, R.B. (2016). "Elaphurus davidianus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T7121A22159785. doi:. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/7121/22159785. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "Conserving Biological Resources". Environmental Science: Systems and Solutions (5th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2013. ISBN 978-1-4496-6139-7. OCLC 777948078. https://books.google.com/books?id=hBntufCOxAsC&pg=PA318.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Press. 2009. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9. OCLC 455328678.

حوالي جي چڪ: "lower-alpha" نالي جي حوالن جي لاءِ ٽيگ <ref> آهن، پر لاڳاپيل ٽيگ <references group="lower-alpha"/> نہ مليو

- اھي صفحا جيڪي سانچن جي سڏن ۾ ٻٽيون شيون استعمال ڪن ٿا

- غيرمددي پيراميٽر سان حوالا تي مشتمل صفحا

- مضمون with short description

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- بهترين مضمون

- اڻٺڄاتل پيراميٽر سان ڄاڻخانو آباد ماڳ کي استعمال ڪندڙ صفحا

- Pages using infobox settlement with the image parameter

- سانچا

- LCCN سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- GND سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- BNF سان سڃاڻپ ڪندڙ وڪيپيڊيا مضمون

- Mammals

- Bathonian first appearances

- Extant Middle Jurassic first appearances

- Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus

- مماليا

- حيوانات

- ڪرنگھيدار جانور

- حوالن ۾ چُڪَ وارا صفحا

- Pages with reference errors that trigger visual diffs