مالي

ڏيک

ريپبلڪ آف مالي | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

شُعار: '"Un peuple, un but, une foi" (فرانسيسي) "ھڪ ماڻھو، ھڪ مقصد ، ھڪ يقين ." | |||||

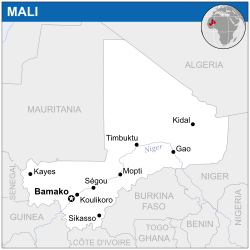

مڪانيت مالي (سائي رنگ وارو) | |||||

| |||||

| گادي جو هنڌ | بماڪو 12°39′N 8°0′W / 12.650°N 8.000°W | ||||

| سڀ کان وڏو شهر | بماڪو | ||||

| دفتري ٻوليون | فرينچ | ||||

| لنگئا فرينڪا | بامبارا | ||||

| قومي ٻوليون | |||||

| نسلي گروھ | |||||

| مقامي آبادي | ماليئن | ||||

| حڪومت | وحداني نيم صدارتي ريپبلڪ | ||||

• صدر |

ابراھيم بوبڪر ڪيئتا | ||||

• وزيراعظم |

Boubou Cisse[2] | ||||

| Issaka Sidibé | |||||

| مقننه | National Assembly | ||||

| آزادي: سوڊان، مالي ۽ سينيگال جي گڏيل وفاق طور | |||||

• فرانس کان |

20 جون 1960 | ||||

• مالي جي نالي سان قيام |

22 سيپٽمبر 1960 | ||||

| پکيڙ | |||||

• جملي |

1٬240٬192 km2 (478٬841 sq mi) (23rd) | ||||

• پاڻي (%) |

1.6 | ||||

| آبادي | |||||

• November 2018 مردم شماري |

19,329,841[3] (67th) | ||||

• گھاٽائي |

11.7 /km2 (30.3 /sq mi) (215th) | ||||

| جِي ڊي پي (مساوي قوت خريد ) | 2018 لڳ ڀڳ | ||||

• ڪل |

$44.329 billion[4] | ||||

• في سيڪڙو |

$2,271[4] | ||||

| جِي. ڊي. پي (رڳو نالي ۾ ) | 2018 لڳ ڀڳ | ||||

• ڪل |

$17.407 ارب ڊالر [4] | ||||

مالي(انگريزي: Mali ) جو سرڪاري نالو ريپبلڪ آف مالي يا جمهوريه مالي آھي. پکيڙ ۾ آفريڪا جو اٺون وڏو ملڪ آهي. ان جي پکيڙ 12,40,000 چورس ڪلوميٽر آهي ۽ آبادي 2018 جي تخميني مطابق 19,329,841 آھي[8]

ملڪ جو گاديءَ جو هنڌ بماڪو آھي. ملڪ جي انتظامي ورھاست اٺ صوبن ۾ ٿيل آهي. اتريون پاسو صحارا رڻپٽ جو حصو اٿس ۽ آبادي ڏکڻ ۾ رھي ٿي جتي درياء نائيجر ۽ درياء سينگال وھن ٿا. ملڪ جي معيشت زرعي آھي.

حوالا

[سنواريو]- ↑ Presidency of Mali: Symboles de la République, L'Hymne National du Mali. Koulouba.pr.ml. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ "Mali president appoints new Prime Minister, Boubou Cisse". https://www.africanews.com/2019/04/23/mali-president-appoints-new-prime-minister-boubou-cisse/. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ↑ "Mali preliminary 2018 census". Institut National de la Statistique. وقت 18 April 2010 تي اصل کان آرڪائيو ٿيل. حاصل ڪيل 29 November 2018. Unknown parameter

|url-status=ignored (مدد) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Mali". International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ "Gini Index". World Bank. حاصل ڪيل 2 March 2011.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. حاصل ڪيل 10 December 2019.

- ↑ Which side of the road do they drive on? Brian Lucas. August 2005. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ↑ Index Mundi using CIA World Factbook statistics, January 20, 2018, retrieved April 13, 2019