دوري جدول

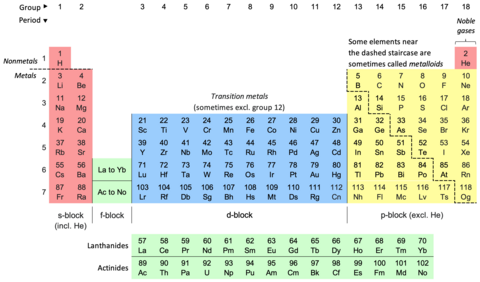

دوري جدول (Periodic Table) جنهن کي عنصرن جي دوري جدول پڻ چيو ويندو آهي سا ڪيميائي عنصرن جي قطارن (Periods) ۽ ڪالمن (Groups) ۾ هڪ جدولي پيشڪش آهي. اهو ڪيميا جو هڪ آئڪن آهي ۽ وڏي پيماني تي فزڪس ۽ ٻين سائنسن ۾ استعمال ٿيندو آهي. قطار ۾ عنصر انهن جي ايٽمي انگن جي ترتيب سان ترتيب ڏنل آهن ۽ ڪالمن ۾ انهن جي خاصيتون ٻيهر ورجائي ظاهر ٿئين تيون. ٽيبل کي چار لڳ ڀڳ مستطيل علائقن ۾ ورهايو ويو آهي، جنهن کي "بلاڪ" سڏجي ٿو. ساڳئي گروپ ۾ عناصر ساڳيون ڪيميائي خاصيتون ڏيکاريندا آهن. ھي جدول ائٽمي نمبر، اليڪٽراني جوڙجڪ ۽ ورجندڙ ڪيميائي خاصيتن جي ڄاڻ ڏيندي آهي.

وقتي ٽيبل هڪ ترتيب ڏنل ترتيب آهي ڪيميائي عناصر کي قطارن (Periods) ۽ ڪالمن (Groups). اهو ڪيميا جو هڪ آئڪن آهي ۽ وڏي پيماني تي فزڪس ۽ ٻين سائنسن ۾ استعمال ٿيندو آهي. اهو دور جي قانون جي هڪ تصوير آهي، جنهن ۾ چيو ويو آهي ته جڏهن عناصر انهن جي ايٽمي انگن جي ترتيب سان ترتيب ڏنل آهن، انهن جي ملڪيت جي تقريبن ٻيهر ورجائي ظاهر ٿئي ٿي.

ٽيبل کي چار لڳ ڀڳ مستطيل علائقن ۾ ورهايو ويو آهي، جنهن کي "بلاڪ" سڏجي ٿو. ساڳئي گروپ ۾ عناصر ساڳيون ڪيميائي خاصيتون ڏيکاريندا آهن. عمودي، افقي ۽ ويڪرائي رجحانات دورانياتي جدول جي خصوصيت ڪن ٿا. دھاتي ڪردار هڪ گروپ جي هيٺان ۽ هڪ دور ۾ ساڄي کان کاٻي طرف وڌندو آهي. نان ميٽالڪ ڪردار وڌندو آهي دوراني جدول جي هيٺان کاٻي پاسي کان مٿي ساڄي طرف. پھرين دوري جدول جيڪا عام طور تي قبول ڪئي وئي، جيڪا 1869ع ۾ روسي ڪيمسٽ دمتري مينڊيليف جي ھئي؛ هن ايٽمي ماس تي ڪيميائي ملڪيتن جي انحصار جي طور تي دورياتي قانون ٺاهيو. جيئن ته ان وقت سڀ عنصر سڃاتل نه هئا، ان ڪري هن جي دور جي جدول ۾ خال هئا، ۽ مينڊيليف ڪاميابيءَ سان دورياتي قانون کي استعمال ڪيو ته جيئن ڪجهه غائب عنصرن جي ملڪيتن جي اڳڪٿي ڪئي وڃي. 19 صدي عيسويء جي آخر ۾ دورياتي قانون کي هڪ بنيادي دريافت طور تسليم ڪيو ويو. ان جي وضاحت 20 صدي جي شروعات ۾ ڪئي وئي، ايٽمي انگن جي دريافت ۽ ڪوانٽم ميڪانڪس ۾ لاڳاپيل اڳڀرائي واري ڪم سان، ٻئي نظريا ايٽم جي اندروني ڍانچي کي روشن ڪرڻ لاءِ ڪم ڪن ٿا. 1945ع ۾ گلين ٽي. سيبورگ جي دريافت سان جدول جي جديد شڪل کي تسليم ڪيو ويو ته ايڪٽائنائيڊ حقيقت ۾ ڊي-بلاڪ عنصرن جي بجاءِ ايف-بلاڪ هئا. دوري جدول ۽ قانون هاڻي جديد ڪيميا جو مرڪزي ۽ لازمي حصو آهن.

The periodic table, also known as the periodic table of the elements, is an ordered arrangement of the chemical elements into rows ("periods") and columns ("groups"). It is an icon of chemistry and is widely used in physics and other sciences. It is a depiction of the periodic law, which states that when the elements are arranged in order of their atomic numbers an approximate recurrence of their properties is evident. The table is divided into four roughly rectangular areas called blocks. Elements in the same group tend to show similar chemical characteristics.

Vertical, horizontal and diagonal trends characterize the periodic table. Metallic character increases going down a group and from right to left across a period. Nonmetallic character increases going from the bottom left of the periodic table to the top right.

The first periodic table to become generally accepted was that of the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869; he formulated the periodic law as a dependence of chemical properties on atomic mass. As not all elements were then known, there were gaps in his periodic table, and Mendeleev successfully used the periodic law to predict some properties of some of the missing elements. The periodic law was recognized as a fundamental discovery in the late 19th century. It was explained early in the 20th century, with the discovery of atomic numbers and associated pioneering work in quantum mechanics, both ideas serving to illuminate the internal structure of the atom. A recognisably modern form of the table was reached in 1945 with Glenn T. Seaborg's discovery that the actinides were in fact f-block rather than d-block elements. The periodic table and law are now a central and indispensable part of modern chemistry.

The periodic table continues to evolve with the progress of science. In nature, only elements up to atomic number 94 exist;[lower-alpha 1] to go further, it was necessary to synthesize new elements in the laboratory. By 2010, the first 118 elements were known, thereby completing the first seven rows of the table;[1] however, chemical characterization is still needed for the heaviest elements to confirm that their properties match their positions. New discoveries will extend the table beyond these seven rows, though it is not yet known how many more elements are possible; moreover, theoretical calculations suggest that this unknown region will not follow the patterns of the known part of the table. Some scientific discussion also continues regarding whether some elements are correctly positioned in today's table. Many alternative representations of the periodic law exist, and there is some discussion as to whether there is an optimal form of the periodic table.

حوالا

[سنواريو]- ↑ "Periodic Table of Elements". IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. حاصل ڪيل 11 May 2024.

حوالي جي چڪ: "lower-alpha" نالي جي حوالن جي لاءِ ٽيگ <ref> آهن، پر لاڳاپيل ٽيگ <references group="lower-alpha"/> نہ مليو